Social Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Risk and Survival: A Systematic Review

A B S T R A C T

Social determinants of health that have been examined in relation to myocardial infarction incidence and survival include socioeconomic status (income, education), neighbourhood disadvantage, immigration status, social support, and social network. Other social determinants of health include geographic factors such as neighbourhood access to health services. Socioeconomic factors influence risk of myocardial infarction. Myocardial infarction incidence rates tend to be inversely associated with socioeconomic status. In addition, studies have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with increased risk of poorer survival. There are well-documented disparities in myocardial infarction survival by socioeconomic status, race, education, and census-tract-level poverty. The results of this review indicate that social determinants such as neighbourhood disadvantage, immigration status, lack of social support, and social isolation also play an important role in myocardial infarction risk and survival. To address these social determinants and eliminate disparities, effective interventions are needed that account for the social and environmental contexts in which heart attack patients live and are treated.

Keywords

Education, myocardial infarction, immigration, poverty, social support

Introduction

Social determinants of health that have been examined in relation to myocardial infarction incidence and survival include socioeconomic status (income, education), neighborhood disadvantage, immigration status, social support, and social network [1-3]. Other social determinants of health include geographic factors such as neighborhood access to health services. Socioeconomic factors such as lack of education, poverty, and income inequality are among the most important social determinants of cardiovascular health [4]. Low-income people are at increased risk of an array of adverse health outcomes, including myocardial infarction, reinfarction, and CHD mortality [5]. The reasons why low-income persons are at increased risk of myocardial infarction may include differences in cigarette smoking, hypertension and diabetes, although differences persist after adjustment for cardiac risk factors [6]. It is well established that socioeconomic factors influence risk of myocardial infarction and reinfarction [1, 2, 6-10]. Most studies have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with increased risk of poorer survival. There are well-documented disparities in myocardial infarction survival by socioeconomic status, race, education, and census-tract-level poverty [11]. However, there is a gap in knowledge about the relationships between social determinants of health (e.g., immigration status, social support/network, and neighborhood access to health services) and myocardial infarction incidence and survival.

The goal of this review was to examine associations between social determinants of health, such as neighborhood disadvantage, immigration status, social support, and social network and risk of myocardial infarction. Studies were also included that examined risk of reinfarction and mortality among patients who had already suffered an acute myocardial infarction.

Methods

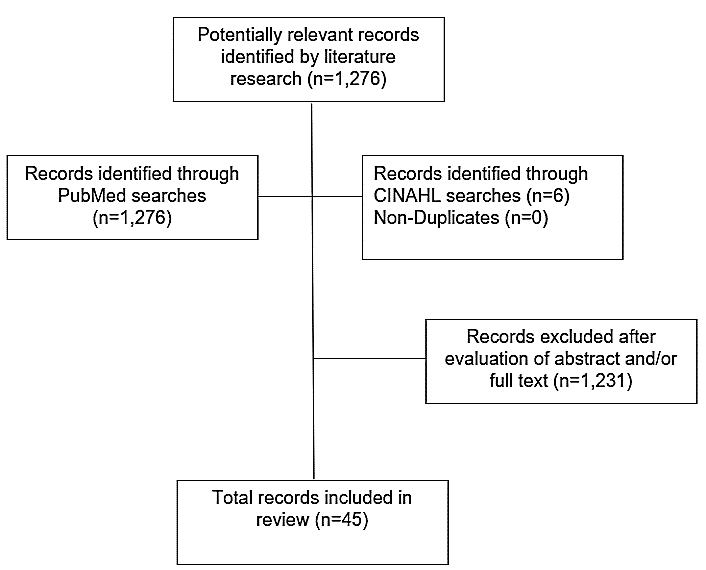

The purpose of this review is to examine the associations between neighborhood deprivation, immigration status, social support and the incidence and survival of myocardial infarction. The neighborhood deprivation refers to community resource deprivation, low-income, lack of education, poor living environment, and crime levels [12]. The social support includes structural support and functional support. The structural support is termed social integration or the social support network (e.g., marital status, single living) [13]. The present review is based upon bibliographic searches in PubMed and CINAHL and relevant search terms. Articles published in English from 1970 through May 1, 2019 were identified using the following MeSH search terms and Boolean algebra commands: (myocardial infarction OR heart attack) AND (incidence OR mortality OR survival) AND (social determinants OR neighborhood disadvantage OR immigration OR social support OR social network). The searches were not limited to words appearing in the title of an article nor to studies in a particular country or geographic region of the world. The references of review articles were also reviewed. Information obtained from bibliographic searches (title and topic of article, information in abstract, study design, and keywords) was used to determine whether to retain each article identified in this way. Only studies written in English that examined social determinants of myocardial infarction risk and survival were eligible for inclusion. A total of 1,276 articles were identified in the bibliographic searches. Of these, 45 met the study criteria (Figure 1). A variety of study designs were identified, including case-control studies, cohort studies, and population-based studies.

Figure 1: Flowchart of record selection process.

Table 1: Studies of neighborhood disadvantage and myocardial infarction risk and survival.

|

Author |

Design |

Outcomes |

Sample |

Results |

|

Alter et al., (1999) |

Population-based study in Ontario, Canada |

Total mortality |

51,591 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

A strong inverse association was observed with neighborhood income (p<0.001). Each $10,000 increase in the neighborhood median income was associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of death within one year (hazards ratio [HR] = 0.90, 95% CI 0.86, 0.94). |

|

Tyden et al., (2002) |

Cohort study in Malmo, Sweden |

Total mortality |

Myocardial infarction patients |

The sex- and age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate per 1,000 patient years ranged from 85.5 to 163.6 between residential areas. The area specific relative risk (RR) of death after discharge was associated with a low socioeconomic score (r=0.56, p=0.018). |

|

Stjarne et al., (2004) |

Population-based case-control study in Stockholm, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

1,631 cases of myocardial infarction and matched controls |

The adjusted RR of myocardial infarction was 2.0 (95% CI 1.3, 3.1) for women living in the top quartile of materially deprived areas. For men, the adjusted RR was 1.6 (95% CI 1.2, 2.1). |

|

Stjarne et al., (2006) |

Population-based case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden |

Acute myocardial infarction |

2,246 cases of myocardial infarction and matched controls |

The level of neighborhood socioeconomic resources had a contextual effect on the RR of myocardial infarction. Compared with high-income neighborhoods, the incidence rate ratio in low income neighborhoods was 1.88 (95% CI 1.25, 2.84) for women and 1.52 (95% CI 1.16, 1.99) for men. |

|

Chaix et al., (2007) |

Cohort study in the Scania region, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction and death from IHD |

52,084 persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

The incidence of myocardial infarction increased with neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation. For high vs. low neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, the hazard ratio (HR) was 1.7 (95% CI 1.4, 2.0). A similar pattern was seen for IHD mortality. |

|

Beard et al., (2008) |

Population-based study in New South Wales, Australia |

Deaths from acute myocardial infarction and hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome |

Persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome |

Area-level socioeconomic disadvantage (defined using Census variables relating to education, occupation, non-English speaking background, indigenous origin, and household economic resources) was related to mortality (RR for highest quartile of disadvantage relative to lowest = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.27, 1.54). |

|

Rose et al, (2009) |

Population-based cohort study in four U.S. communities |

Incident hospitalized myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk of incident hospitalized myocardial infarction |

Within each community, and among all race-gender groups, those living in low neighborhood median household income neighborhoods had an increased risk of myocardial infarction compared to those living in high neighborhood median household income neighborhoods. |

|

Davies et al., (2009) |

Population-based study in Scotland |

Incident acute myocardial infarction |

5.1 million persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction |

The socioeconomic gradient in acute myocardial infarction increased over time (p<0.001). Among males, the gradient across area deprivation categories in 1990-1992 was most pronounced at younger ages. The RR of acute myocardial infarction in the most deprived areas compared to the least was 2.6 (95% CI 1.6, 4.3) for those aged 45-59 years and 1.6 (95% CI 1.1, 2.5) at 60-74 years. A similar pattern was seen in women. |

|

Gerber et al. (2010) |

Cohort study of patients discharged from 8 Israeli hospitals |

Total mortality and cardiac mortality |

1,179 patients with incident myocardial infarction |

Patients residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods had higher mortality rates, with 13-year survival estimates of 61%, 74%, and 82% in increasing tertiles (p-trend < 0.001). The HRs for death associated with neighborhood socioeconomic status were 1.47 (95% CI 1.05, 2.06) in the lower tertile and 1.19 (95% CI 0.86, 1.63) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile (p-trend = 0.02). |

|

Henriksson et al., (2010) |

Population-based study in Sweden municipalities |

Acute myocardial infarction and total mortality

|

Persons at risk for acute myocardial infarction |

Risk for acute myocardial infarction was lower in the municipalities with higher degree of income inequality. |

|

Deguen et al., (2010) |

Population-based study in Strasbourg metropolitan area, France |

Myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

The risk of myocardial infarction increased with the neighborhood deprivation level. Women appeared to be more susceptible at levels of extreme deprivation. |

|

Blais et al., (2012) |

Population-based study in Quebec |

Total mortality |

50,242 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Based upon a population deprivation index, the most materially and socially deprived patients had a 16% (95% CI 1.08, 1.25) and 13% (95% CI 1.05, 1.21) relative increased hazard of dying within 1 year, respectively, compared with the most privileged subjects. |

|

Koren et al., (2012) |

Hospital-based cohort study in Israel |

Recurrent myocardial infarction

|

1,164 patients with incident myocardial infarction |

The hazards of recurrent myocardial infarction was higher in low socioeconomic status neighborhoods (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.13, 2.14). |

|

Koopman et al., (2012) |

Population-based cohort study in The Netherlands. |

Incident acute myocardial infarction

|

Persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction |

When comparing the most deprived neighborhood-level socioeconomic quintile with the most affluent quintile, the overall RR for acute myocardial infarction was 1.34 (95% CI 1.32, 1.36) in men and 1.44 (95% CI 1.42, 1.47) in women. |

|

Kim et al., (2014) |

Retrospective cohort study at one referral center in South Korea |

Total mortality |

2,358 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

No significant association was seen between a neighborhood socioeconomic status indicator (social deprivation index) and mortality. |

|

Thorne et al., (2015) |

Record linkage study in Wales |

30-day mortality following acute myocardial infarction |

Patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Social deprivation was significantly associated with higher mortality for acute myocardial infarction. |

|

Kim et al., (2018) |

Quasi-experimental study in Toronto, Canada area |

Incident myocardial infarction and total mortality |

Residents of public housing |

Living in a public housing project in the second highest neighborhood socioeconomic position was non-significantly associated with lower hazards of acute myocardial infarction (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.54, 1.07, p = 0.11) and all-cause mortality (HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.73, 1.01, p=0.06). |

Results

I Neighborhood Disadvantage and Myocardial Infarction

Neighborhood disadvantage is defined as overall low neighborhood education, income, living resource deprivation. Alter et al. conducted a population-based study of 51,591 patients with acute myocardial infarction in Ontario, Canada (Table 1) [14]. A strong inverse association was observed with neighborhood income (p<0.001). Each $10,000 increase in the neighborhood median income was associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of death within one year (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.90, 95% CI 0.86, 0.94). Stjarne et al. examined the relation between area material deprivation and risk of myocardial infarction in a population-based case-control study in Stockholm, Sweden [15]. The adjusted relative of myocardial infarction was 2.0 (95% CI 1.3, 3.1) for women living in the top quartile of materially deprived areas. For men, the adjusted relative risk was 1.6 (95% CI 1.2, 2.1).

In a population-based case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden, Stjarne et al. examined the relation between neighborhood socioeconomic resources and risk of acute myocardial infarction [16]. The level of neighborhood socioeconomic resources had a contextual effect on the relative risk of myocardial infarction. Compared with high-income neighborhoods, the incidence rate ratio in low-income neighborhoods was 1.88 (95% CI 1.25, 2.84) for women and 1.52 (95% CI 1.16, 1.99) for men. Chaix et al. examined the relation between neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and risk of myocardial infarction in a cohort study of 52,084 persons in the Scania region of Sweden [17]. The incidence of myocardial infarction increased with neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation. For high vs. low neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, the hazard ratio was 1.7 (95% CI 1.4, 2.0). A similar pattern was seen for ischaemic heart disease mortality.

In a population-based study in New South Wales, Australia, Beard et al. examined the relation between area socioeconomic disadvantage and death from acute myocardial infarction [18]. Area-level socioeconomic disadvantage (defined using Census variables relating to education, occupation, non-English speaking background, indigenous origin, and household economic resources) was related to mortality (relative risk for highest quartile of disadvantage relative to lowest = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.27, 1.54). In a population-based cohort study in four U.S. communities, Rose et al. examined the relation between neighborhood median household income and risk of myocardial infarction [19]. Within each community, and among all race-gender groups, those living in low neighborhood median household income neighborhoods had an increased risk of myocardial infarction compared to those living in high neighborhood median household income neighborhoods.

Davies et al. conducted a population-based study of area deprivation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in Scotland [20]. The socioeconomic gradient in acute myocardial infarction increased over time (p<0.001). Among males, the gradient across area deprivation categories in 1990-1992 was most pronounced at younger ages. The relative risk of acute myocardial infarction in the most deprived areas compared to the least was 2.6 (95% CI 1.6, 4.3) for those aged 45-59 years and 1.6 (95% CI 1.1, 2.5) at 60-74 years. A similar pattern was seen in women. Gerber et al. conducted a cohort study of 1,179 myocardial infarction patients discharged from 8 Israeli hospitals [21]. Patients residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods had higher mortality rates, with 13-year survival estimates of 61%, 74%, and 82% in increasing tertiles (p-trend < 0.001). The hazard ratios for death associated with neighborhood socioeconomic status were 1.47 (95% CI 1.05, 2.06) in the lower tertile and 1.19 (95% CI 0.86, 1.63) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile (p-trend = 0.02).

Henriksson et al. examined the relation between municipality income inequality and risk of acute myocardial infarction in a population-based study in Sweden [22]. Risk for acute myocardial infarction was lower in the municipalities with higher degree of income inequality. In a population-based study in Strasbourg metropolitan area in France, Deguen et al. examined the relation between level of neighborhood deprivation and risk of myocardial infarction [23]. The risk of myocardial infarction increased with the neighborhood deprivation level. Women appeared to be more susceptible at levels of extreme deprivation. Blais et al. conducted a population-based study of 50,242 patients with acute myocardial infarction in Quebec, Canada [24]. Based upon a population deprivation index, the most materially and socially deprived patients had a 16% (95% CI 1.08, 1.25) and 13% (95% CI 1.05, 1.21) relative increased hazard of dying within 1 year, respectively, compared with the most privileged subjects.

In a hospital-based cohort study in Israel, Koren et al. examined the relation between neighborhood socioeconomic status and risk of recurrent myocardial infarction [25]. The hazards of recurrent myocardial infarction were higher in low socioeconomic status neighborhoods (hazard ratio = 1.55, 95% CI 1.13, 2.14). Koopman et al. examined the relation between neighborhood deprivation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in a population-based cohort study in The Netherlands [26]. When comparing the most deprived neighborhood-level socioeconomic quintile with the most affluent quintile, the overall relative risk for acute myocardial infarction was 1.34 (95% CI 1.32, 1.36) in men and 1.44 (95% CI 1.42, 1.47) in women. Kim et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study of acute myocardial infarction patients as one referral center in South Korea [27]. No significant association was seen between a neighborhood socioeconomic status indicator (social deprivation index) and mortality.

In a record linkage study in Wales, Thorne et al. examined the relation between area social deprivation and 30-day mortality following acute myocardial infarction [28]. Social deprivation was significantly associated with higher mortality for acute myocardial infarction. In a quasi-experimental study in the Toronto, Canada area, Kim et al. examined the relation between neighborhood socioeconomic position and risk of myocardial infarction and total mortality [29]. Living in a public housing project in the second highest neighborhood socioeconomic position was non-significantly associated with lower hazards of acute myocardial infarction (hazard ratio = 0.76, 95% CI 0.54, 1.07, p = 0.11) and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio = 0.86, 95% CI 0.73, 1.01, p=0.06).

Table 2: Studies of immigration status and myocardial infarction risk and survival.

|

Author |

Design |

Outcomes |

Sample |

Results |

|

Alfredsson et al., (1982) |

Case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

356 cases and matched controls |

The overall RR for Finnish immigrants compared to native Swedes was 1.7. For the group of Finnish immigrants who had been in Sweden for 20 years or more the RR was 1.3. |

|

Hedlund et al., (2007) |

Case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

46,366 cases of incident myocardial infarction and stratified controls |

Foreign-born subjects had a higher incidence of myocardial infarction than those born in Sweden (RR for men = 1.17, 95% CI 1.13, 1.21; RR for women = 1.15, 95% CI 1.09, 1.21). An increased incidence was present primarily in subjects born in Finland, other Nordic countries, Poland, Turkey, Syria and South Asia in both genders, from the Netherlands among men, and from Iraq among women. |

|

Hedlund et al., (2008) |

Population-based cohort study in Stockholm, Sweden |

Total mortality |

Incident cases of myocardial infarction |

After adjustment for socioeconomic status, male immigrants had a lower mortality within 28 days after a first myocardial infarction compared to Sweden-born (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.76, 0.94). Among women, there was a weak similar relationship (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.76, 1.10). There were no important differences between foreign-born and Sweden-born in 1-year mortality. |

|

Saposnik et al.,(2010) |

Population-bases, matched, retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada |

Hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk for myocardial infarction |

The incidence rate of acute myocardial infarction was 4.14 per 10,000 persons among new immigrants and 6.61 per 10,000 person-years among long-term residents (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.63, 0.69). |

|

Hempler et al., (2011) |

Registry-based follow-up study in Denmark |

Incident acute myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction |

Immigrant men and women from Turkey and Pakistan had an increased incidence of acute myocardial infarction. No notable differences were observed between former Yugoslavians and native Danes. |

|

Deckert et al., (2013) |

Retrospective cohort study in Germany |

Total mortality and acute myocardial infarction incidence

|

Persons at risk for acute myocardial infarction |

Acute myocardial infarction incidence was higher in male repatriates (standardized incidence ratio = 1.30, 95% CI 1.02, 1.65) than in the general German population. |

|

van Oeffelen et al., (2014) |

Population-based cohort study in The Netherlands |

Acute myocardial infarction and total mortality

|

Persons hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Mortality and acute myocardial infarction readmission rates were higher among immigrants as compared with ethnic Dutch. |

|

Dzayee et al.., (2014) |

Nationwide cohort study in Sweden |

Recurrent myocardial infarction |

518,503 patients diagnosed with first myocardial infarction |

Foreign-born men and women had a slightly increased HR than Sweden-born men and women. Foreign-born who had lived in Sweden for less than 35 years had a higher risk than those who had lived there for 35 years or longer. |

|

Shvartsur et al., (2018) |

Retrspective cohort study in Israel |

Total mortality |

11,143 Israeli-born and immigrant acute myocardial infarction patients |

10-year mortality rates were 65% lower in Israeli-born patients compared with immigrants. |

II Immigration Status and Myocardial Infarction

In a case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden, Alfredsson et al. examined the relation between immigration status and risk of myocardial infarction, as shown in (Table 2) [30]. The overall relative risk for Finnish immigrants compared to native Swedes was 1.7. For the group of Finnish immigrants who had been in Sweden for 20 years or more, the relative risk was 1.3. Hedlund et al. examined the relation between immigration status and risk of myocardial infarction in a case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden [31]. Foreign-born subjects had a higher incidence of myocardial infarction than those born in Sweden (relative risk for men = 1.17, 95% CI 1.13, 1.21; relative risk for women = 1.15, 95% CI 1.09, 1.21). An increased incidence was present primarily in subjects born in Finland, other Nordic countries, Poland, Turkey, Syria and South Asia in both genders, from the Netherlands among men, and from Iraq among women.

In a population-based cohort study of myocardial infarction patients in Stockholm, Sweden, Hedlund et al. examined the relation between immigration status and total mortality [32]. After adjustment for socioeconomic status, male immigrants had a lower mortality within 28 days after a first myocardial infarction compared to Sweden-born (odds ratio = 0.84, 95% CI 0.76, 0.94). Among women, there was a weak similar relationship (odds ratio = 0.92, 95% CI 0.76, 1.10). There were no important differences between foreign-born and Sweden-born in 1-year mortality. In a population-based, matched, retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada, Saposnik et al. examined the relation between immigration and hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction [33]. The incidence rate of acute myocardial infarction was 4.14 per 10,000 persons among new immigrants and 6.61 per 10,000 person-years among long-term residents (hazard ratio = 0.66, 95% CI 0.63, 0.69). Hempler et al. examined the relation between immigration status and risk of acute myocardial infarction in a registry-based follow-up study in Denmark [34]. Immigrant men and women from Turkey and Pakistan had an increased incidence of acute myocardial infarction. No notable differences were observed between former Yugoslavians and native Danes.

In a retrospective cohort study in Germany, Decker et al. examined the relation between repatriation status and risk of acute myocardial infarction [35]. Acute myocardial infarction incidence was higher in male repatriates (standardized incidence ratio = 1.30, 95% CI 1.02, 1.65) than in the general German population. In a population-based cohort study in The Netherlands, Van Oeffelen et al. examined the relation between immigration status and myocardial infarction readmission rates and mortality [36]. Mortality and acute myocardial infarction readmission rates were higher among migrants as compared with ethnic Dutch. Dzayee et al. examined the relation between immigration status and recurrent myocardial infarction in a nationwide cohort study in Sweden [37]. Foreign-born men and women had a slightly increased hazard ratio than Sweden-born men and women. Foreign-born who had lived in Sweden for less than 35 years had a higher risk than those who had lived there for 35 years or longer. Shvartsur et al. examined the relation between immigration status and total mortality in a retrospective cohort study of acute myocardial infarction patients in Israel [38]. Ten-year mortality rates were 65% lower in Israeli-born patients compared with immigrants.

III Social Support and Myocardial Infarction

Berkman et al. examined the relation between emotional support and total mortality in a cohort study of patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction in New Haven, CT (Table 3) [39]. Lack of emotional support was significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio = 2.9, 95% CI 1.2, 6.9). In a cohort study in England, Jenkinson et al. examined the relation between social isolation and mortality among 1,376 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction [40]. Socially isolated patients were 49% more likely to die after an infarction than patients who were not socially isolated. Friedmann and Thomas examined the relation between social support and total mortality in a follow-up study of patients with myocardial infarction [41]. High social support tended to predict survival independently of demographic and other psychosocial variables (p<0.068).

Table 3: Studies of social support and myocardial infarction risk and survival.

|

Author |

Design |

Outcomes |

Sample |

Results |

|

Berkman et al., (1992) |

Cohort study in New Haven, CT |

Total mortality |

194 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Lack of emotional support was significantly associated with mortality (OR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.2, 6.9). |

|

Jenkinson et al., (1993)

|

Cohort study in England |

Total mortality |

1,376 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Socially isolated patients were 49% more likely to die after an infarction than patients who were not socially isolated. |

|

Friedmann & Thomas, (1995) |

Follow-up study of randomized controlled trial participants |

Total mortality |

368 myocardial infarction patients |

High social support tended to predict survival independently of demographic and other psychosocial variables (p<0.068). |

|

Greenwood et al., (1995) |

Cohort study in England |

Total mortality |

1,701 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Lack of social contacts or being unmarried were not significantly associated with survival. |

|

Farmer et al., (1996) |

Cohort study in Corpus Christi, TX |

Total mortality |

596 patients with myocardial infarction |

Survival following myocardial infarction was greater for those with high or medium social support than for those with low social support. The RR of mortality was 1.89 (95% CI 1.20, 2.97) for those with low social support. |

|

Hammer et al., (1998) |

Population-based case-control study in five Swedish counties |

Incident myocardial infarction |

Men and women in five counties in Sweden who were at risk of myocardial infarction |

Younger men (30-54 years of age) in occupations with both high job strain and low social support at work had a RR of 1.79 (95% CI 1.22, 2.65) compared with subjects in low strain and high social support jobs. |

|

Pederson et al., (2004) |

Follow-up study of patients 4-6 weeks post- myocardial infarction and at 9 months |

Recurrent cardiac events |

112 myocardial infarction patients treated at two hospitals in Denmark |

Lower social support at baseline was associated with an increased risk of recurrent cardiac events at follow-up (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.84, 0.97). |

|

Andre-Petersson et al., (2006) |

Cohort study of men in Malmo, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction and total mortality |

Men born in Malmo, Sweden who were at-risk of myocardial infarction |

Low levels of social support was associated with an increased risk of incident myocardial infarction (HR = 2.40, 95% CI 1.36, 4.25, p = 0.003) and premature death (HR = 1.99, 95% CI 1.32, 3.00, p = 0.001). |

|

Schmaltz et al., (2007) |

Study of all patients discharged with a primary diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction from three medical centers in Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

Mortality |

Patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Living alone was independently associated with mortality (adjusted HR = 1.6, 95% CI 1.0, 2.5), but interacted with patient sex. Men living alone had the highest mortality risk (HR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.1, 3.7), followed by women living alone, men living with others, and women living with others. |

|

Chaix et al., (2006) |

Cohort study of men in Malmo, Sweden |

Acute myocardial infarction and death due to chronic IHD |

498 men at risk of acute myocardial infarction or death due to IHD |

Low neighborhood-based social support was associated with increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and IHD mortality. The hazard ratios for IHD death associated with neighborhood social support were 2.50 (95% CI 1.06, 5.91) in the lower tertile and 1.66 (95% CI 0.70, 3.93) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile. The hazard ratios for incident myocardial infarction associated with neighborhood social support were 1.87 (95% CI 1.02, 3.43) in the lower tertile and 1.60 (95% CI 0.89, 2.86) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile. |

|

Andre-Petersson et al., (2007) |

Cohort study in Malmo, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

7,770 men and women at risk of myocardial infarction |

Among women, low levels of social support at work was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. No association was observed among men. |

|

Lett et al., (2007) |

Prospective study of randomized controlled trial participants |

Total mortality and non-fatal reinfarction |

1,481 acute myocardial infarction patients |

Higher levels of perceived social support were associated with improved outcome for patients without elevated depression but not for patients with high levels of depression. The relation between perceived social support and mortality or nonfatal infarction did not reach statistical significance. |

|

Nielsen & Mard, (2010) |

Cohort study in Denmark |

Total mortality |

242 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Single living was an independent predictor of death (HR = 2.55, 95% CI 1.52, 4.30). |

|

Bucholz et al., (2011) |

Registry-based cohort study at 19 U.S. medical centers |

Acute myocardial infarction and 4-year mortality |

Patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Patients who lived alone had a comparable risk of mortality (HR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.76, 1.28) as patients who lived with others. |

|

Kitamura et al., (2013) |

Cohort study in Osaka region of Japan |

Major adverse cardiovascular events and total mortality |

5,845 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Living alone was associated with a higher risk of composite endpoint consisting of major adverse cardiovascular events and total deaths (HR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.11, 1.58). |

|

Gafarov et al., (2013) |

Cohort study |

Incident myocardial infarction |

870 women in Novosibirsk, Russia |

The rate of myocardial infarction was higher in married women with fewer close contacts and smaller social networks. |

|

Quinones et al., (2014) |

Registry-based cohort study in Augsburg, Germany |

Total mortality |

3,766 patients with incident myocardial infarction |

Overall, marital status showed a statistically non-significant inverse association (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.47, 1.22). Stratified analyses revealed strong protective effects only among men and women aged < 60 years who were diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. |

|

Kilpi et al., (2015) |

Population-based cohort study in Finland |

Myocardial infarction incidence and mortality |

302,885 persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

Men who were married had a lower risk of myocardial infarction as compared with those who were unmarried, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors. Among women, the associations of living arrangements with myocardial infarction were explained by socioeconomic factors. Living arrangements were strong predictors of survival after myocardial infarction. |

|

Weiss-Faratci et al., (2016) |

Cohort study in Israel |

Total mortality at two time points |

Patients with incident myocardial infarction |

Higher perceived social support was associated with lower mortality at both time points (HR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.75, 0.96; HR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.66, 0.83, respectively). |

|

Hakulinen et al., (2018) |

Cohort study in the United Kingdom |

Incident acute myocardial infarction and total mortality |

479,054 persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

Social isolation was associated with higher risk of acute myocardial infarction (HR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.3-1.55). |

In a cohort study of patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction in England, Greenwood et al. examined the relation between lack of social contacts or being unmarried and total mortality [42]. Lack of social contacts or being unmarried was not significantly associated with survival. In a cohort study of 596 patients with myocardial infarction in Corpus Christi, TX, Farmer et al. examined the relation between social support and total mortality [43]. Survival following myocardial infarction was greater for those with high or medium social support than for those with low social support. The relative risk of mortality was 1.89 (95% CI 1.20, 2.97) for those with low social support. In a population-based case-control study in five Swedish counties, Hammer et al. examined the relation between social support and risk of myocardial infarction [44]. Younger men (30-54 years of age) in occupations with both high job strain and low social support at work had a relative risk of 1.79 (95% CI 1.22, 2.65) compared with subjects in low strain and high social support jobs.

In a follow-up study of 112 myocardial infarction patients treated at two hospitals in Denmark, Pederson et al. examined the relation between social support and recurrent cardiac events [45]. Lower social support at baseline was associated with an increased risk of recurrent cardiac events at follow-up (odds ratio = 0.90, 95% CI 0.84, 0.97). Andre-Petersson et al. examined the relation between social support and risk of myocardial infarction and total mortality in a cohort study in Malmo, Sweden [46]. Low levels of social support was associated with an increased risk of incident myocardial infarction (hazard ratio = 2.40, 95% CI 1.36, 4.25, p = 0.003) and premature death (hazard ratio = 1.99, 95% CI 1.32, 3.00, p = 0.001). In a study of all patients discharged with a primary diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction from three medical centers in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, Schmaltz et al. examined the relation between living alone and mortality [47]. Living alone was independently associated with mortality (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.6, 95% CI 1.0, 2.5), but interacted with patient sex. Men living alone had the highest mortality risk (hazard ratio = 2.0, 95% CI 1.1, 3.7), followed by women living alone, men living with others, and women living with others.

In a cohort study in Malmo, Sweden, Chaix et al. examined the relation between neighborhood-based social support and risk of acute myocardial infarction and death due to chronic ischaemic heart disease (IHD) [48]. Low neighborhood-based social support was associated with increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and IHD mortality. The hazard ratios for IHD death associated with neighborhood social support were 2.50 (95% CI 1.06, 5.91) in the lower tertile and 1.66 (95% CI 0.70, 3.93) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile. The hazard ratios for incident myocardial infarction associated with neighborhood social support were 1.87 (95% CI 1.02, 3.43) in the lower tertile and 1.60 (95% CI 0.89, 2.86) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile.

In a cohort study in Malmo, Sweden, Andre-Petersson examined the relation between social support and risk of myocardial infarction [49]. Among women, low levels of social support at work was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. No association was observed among men. In a prospective study of acute myocardial infarction patients, Lett et al. examined the relation between perceived social support and total mortality and non-fatal reinfarction [50]. Higher levels of perceived social support were associated with improved outcome for patients without elevated depression but not for patients with high levels of depression. The relation between perceived social support and mortality or non-fatal infarction did not reach statistical significance. In a cohort study of 242 patients with acute myocardial infarction in Denmark, Nielsen and Mard examined the relation between single living and total mortality [51]. Single living was an independent predictor of death (hazard ratio = 2.55, 95% CI 1.52, 4.30).

In a registry-based cohort study of patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction at 19 U.S. medical centers, Bucholz et al. examined the relation between living alone and reinfarction and mortality [52]. Patients who lived alone had a comparable risk of mortality (hazard ratio = 0.99, 95% CI 0.76, 1.28) as patients who lived with others. In a cohort study of 5,845 patients with acute myocardial infarction in the Osaka region of Japan, Kitamura et al. examined the relation between living alone and major adverse cardiovascular events and total mortality [53]. Living alone was associated with a higher risk of composite endpoint consisting of major adverse cardiovascular events and total deaths (hazard ratio = 1.32, 95% CI 1.11, 1.58). In a cohort study in Novosibirsk, Russia, Gafarov et al. examined social support and social networks in relation to risk of myocardial infarction [54]. The rate of myocardial infarction was higher in married women with fewer close contacts and smaller social networks.

In a registry-based study of 3,766 patients with incident myocardial infarction in Augsburg, Germany, Quinones et al. examined the relation between marital status and total mortality [55]. Overall, marital status showed a statistically non-significant inverse association (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.47, 1.22). Stratified analyses revealed strong protective effects only among men and women aged < 60 years who were diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. Kipli et al. examined the relation between marital status and risk of myocardial infarction incidence and mortality in a cohort of 302,885 persons in Finland [56]. Men who were married had a lower risk of myocardial infarction as compared with those who were unmarried, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors. Among women, the associations of living arrangements with myocardial infarction were explained by socioeconomic factors. Living arrangements were strong predictors of survival after myocardial infarction.

In a cohort study of patients with incident myocardial infarction in Israel, Weiss-Faratci et al. examined the relation between social support and mortality [57]. Higher perceived social support was associated with lower mortality at both time points (hazard ratio = 0.85, 95% CI 0.75, 0.96; hazard ratio = 0.74, 95% CI 0.66, 0.83, respectively). Hakulinen et al. examined the relation between social isolation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in a cohort study of 479,054 persons in the United Kingdom [58]. Social isolation was associated with higher risk of acute myocardial infarction (hazard ratio = 1.43, 95% CI 1.3-1.55).

Discussion

The results of this review indicate that social determinants such as neighborhood disadvantage (e.g., resource deprivation, poverty, lack of education), immigration status, lack of social support, and social isolation play an important role in myocardial infarction risk and survival. Residing in areas with fewer economic resources may delay care for acute illness or adversely impact the ability to receive follow-up care [1]. Population differences in cardiovascular risk factors such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, and diabetes may partly account for associations between area-based measures of socioeconomic status and neighborhood disadvantage are associated with increased risk of adverse health outcomes. Some but not all studies have shown that myocardial infarction incidence rates are lower among immigrants. The healthy immigrant effect diminishes over several generations. Studies have shown that country of origin is associated with myocardial infarction survival. These differences may be due to environmental exposures such as diet, smoking, or physical activity.

Several factors may account for the inverse association between social support and myocardial infarction survival. First, lack of social support and depression are interrelated. Social isolation provokes anxiety and depression, activating neuroendocrine, immune responses, and hemodynamic alterations via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [59]. These deleterious biological processes are known to damage arterial walls and the myocardium itself [59]. Like other major risk factors of MI (e.g., elevated cholesterol level, tobacco use, and hypertension), the evidence showed social isolation related anxiety and depression elevated the same biomarkers that mediate the effects of elevated cholesterol level or tobacco use [13]. Second, the treatment of acute MI is costly. Adequate social support may help patients gain other supportive resources, such as medical referral networks, group therapy, or informational opportunities relating to financial support [13]. Individuals with adequate social support may also have better access to the appropriate treatment [13]. Third, social support was found as the mediator between self-care behaviours and disease progression [60]. Social support may offer protection against the negative health consequences by enhancing health-promoting behaviours and discouraging negative behaviours. Finally, cardiac rehabilitation programs and other prevention strategies are effective to prevent and reduce mortality post-MI [13]. The cardiac rehabilitation, a group setting program, provides three types of peer support. They are emotional, informational, and affirmational [13]. Peer support has been found effective to relieve anxiety and depression, promote positive coping strategies, improve outlook and confidence in post-MI management, therefore enhance recovery and survival [13].

Rehabilitation provides an opportunity to offer peer support to patients who have a low social support. Based on our review, we recommend to modify rehabilitation program into a more social activity with boosted peer support system in which individuals with low social support can be partnered with volunteers who have well-established social support and experienced in MI management. In addition, social support is not routinely assessed by general practitioners, and even less by cardiovascular specialists. Therefore, screening for social support and depression may be useful to identify high risk induvial and reduce mortality. Although extensive research has shown a consistent relationship between low social support and MI, the mechanism of social support is not clearly identified. The challenge remains to plan and evaluate interventions that target social support. Much more research is required to explicate strategies for modifying the negative effects of this relationship, particularly at the public health level.

To address these social determinants and eliminate myocardial infarction disparities, effective interventions are needed that account for the social and environmental contexts in which patients live and are treated. Of particular concern are access to health care among immigrant populations and health communication about the early detection and treatment of cardiovascular disease risk factors for patients who are unmarried or socially isolated.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Article Info

Article Type

Review ArticlePublication history

Received: Fri 14, Aug 2020Accepted: Mon 31, Aug 2020

Published: Fri 18, Sep 2020

Copyright

© 2023 Steven S. Coughlin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.EJCR.2020.01.02

Author Info

Steven S. Coughlin Lufei Young

Corresponding Author

Steven S. CoughlinDepartment of Population Health Sciences, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, Augusta, GA, USA

Figures & Tables

Table 1: Studies of neighborhood disadvantage and myocardial infarction risk and survival.

|

Author |

Design |

Outcomes |

Sample |

Results |

|

Alter et al., (1999) |

Population-based study in Ontario, Canada |

Total mortality |

51,591 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

A strong inverse association was observed with neighborhood income (p<0.001). Each $10,000 increase in the neighborhood median income was associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of death within one year (hazards ratio [HR] = 0.90, 95% CI 0.86, 0.94). |

|

Tyden et al., (2002) |

Cohort study in Malmo, Sweden |

Total mortality |

Myocardial infarction patients |

The sex- and age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate per 1,000 patient years ranged from 85.5 to 163.6 between residential areas. The area specific relative risk (RR) of death after discharge was associated with a low socioeconomic score (r=0.56, p=0.018). |

|

Stjarne et al., (2004) |

Population-based case-control study in Stockholm, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

1,631 cases of myocardial infarction and matched controls |

The adjusted RR of myocardial infarction was 2.0 (95% CI 1.3, 3.1) for women living in the top quartile of materially deprived areas. For men, the adjusted RR was 1.6 (95% CI 1.2, 2.1). |

|

Stjarne et al., (2006) |

Population-based case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden |

Acute myocardial infarction |

2,246 cases of myocardial infarction and matched controls |

The level of neighborhood socioeconomic resources had a contextual effect on the RR of myocardial infarction. Compared with high-income neighborhoods, the incidence rate ratio in low income neighborhoods was 1.88 (95% CI 1.25, 2.84) for women and 1.52 (95% CI 1.16, 1.99) for men. |

|

Chaix et al., (2007) |

Cohort study in the Scania region, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction and death from IHD |

52,084 persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

The incidence of myocardial infarction increased with neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation. For high vs. low neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, the hazard ratio (HR) was 1.7 (95% CI 1.4, 2.0). A similar pattern was seen for IHD mortality. |

|

Beard et al., (2008) |

Population-based study in New South Wales, Australia |

Deaths from acute myocardial infarction and hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome |

Persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome |

Area-level socioeconomic disadvantage (defined using Census variables relating to education, occupation, non-English speaking background, indigenous origin, and household economic resources) was related to mortality (RR for highest quartile of disadvantage relative to lowest = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.27, 1.54). |

|

Rose et al, (2009) |

Population-based cohort study in four U.S. communities |

Incident hospitalized myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk of incident hospitalized myocardial infarction |

Within each community, and among all race-gender groups, those living in low neighborhood median household income neighborhoods had an increased risk of myocardial infarction compared to those living in high neighborhood median household income neighborhoods. |

|

Davies et al., (2009) |

Population-based study in Scotland |

Incident acute myocardial infarction |

5.1 million persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction |

The socioeconomic gradient in acute myocardial infarction increased over time (p<0.001). Among males, the gradient across area deprivation categories in 1990-1992 was most pronounced at younger ages. The RR of acute myocardial infarction in the most deprived areas compared to the least was 2.6 (95% CI 1.6, 4.3) for those aged 45-59 years and 1.6 (95% CI 1.1, 2.5) at 60-74 years. A similar pattern was seen in women. |

|

Gerber et al. (2010) |

Cohort study of patients discharged from 8 Israeli hospitals |

Total mortality and cardiac mortality |

1,179 patients with incident myocardial infarction |

Patients residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods had higher mortality rates, with 13-year survival estimates of 61%, 74%, and 82% in increasing tertiles (p-trend < 0.001). The HRs for death associated with neighborhood socioeconomic status were 1.47 (95% CI 1.05, 2.06) in the lower tertile and 1.19 (95% CI 0.86, 1.63) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile (p-trend = 0.02). |

|

Henriksson et al., (2010) |

Population-based study in Sweden municipalities |

Acute myocardial infarction and total mortality

|

Persons at risk for acute myocardial infarction |

Risk for acute myocardial infarction was lower in the municipalities with higher degree of income inequality. |

|

Deguen et al., (2010) |

Population-based study in Strasbourg metropolitan area, France |

Myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

The risk of myocardial infarction increased with the neighborhood deprivation level. Women appeared to be more susceptible at levels of extreme deprivation. |

|

Blais et al., (2012) |

Population-based study in Quebec |

Total mortality |

50,242 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Based upon a population deprivation index, the most materially and socially deprived patients had a 16% (95% CI 1.08, 1.25) and 13% (95% CI 1.05, 1.21) relative increased hazard of dying within 1 year, respectively, compared with the most privileged subjects. |

|

Koren et al., (2012) |

Hospital-based cohort study in Israel |

Recurrent myocardial infarction

|

1,164 patients with incident myocardial infarction |

The hazards of recurrent myocardial infarction was higher in low socioeconomic status neighborhoods (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.13, 2.14). |

|

Koopman et al., (2012) |

Population-based cohort study in The Netherlands. |

Incident acute myocardial infarction

|

Persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction |

When comparing the most deprived neighborhood-level socioeconomic quintile with the most affluent quintile, the overall RR for acute myocardial infarction was 1.34 (95% CI 1.32, 1.36) in men and 1.44 (95% CI 1.42, 1.47) in women. |

|

Kim et al., (2014) |

Retrospective cohort study at one referral center in South Korea |

Total mortality |

2,358 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

No significant association was seen between a neighborhood socioeconomic status indicator (social deprivation index) and mortality. |

|

Thorne et al., (2015) |

Record linkage study in Wales |

30-day mortality following acute myocardial infarction |

Patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Social deprivation was significantly associated with higher mortality for acute myocardial infarction. |

|

Kim et al., (2018) |

Quasi-experimental study in Toronto, Canada area |

Incident myocardial infarction and total mortality |

Residents of public housing |

Living in a public housing project in the second highest neighborhood socioeconomic position was non-significantly associated with lower hazards of acute myocardial infarction (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.54, 1.07, p = 0.11) and all-cause mortality (HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.73, 1.01, p=0.06). |

Table 2: Studies of immigration status and myocardial infarction risk and survival.

|

Author |

Design |

Outcomes |

Sample |

Results |

|

Alfredsson et al., (1982) |

Case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

356 cases and matched controls |

The overall RR for Finnish immigrants compared to native Swedes was 1.7. For the group of Finnish immigrants who had been in Sweden for 20 years or more the RR was 1.3. |

|

Hedlund et al., (2007) |

Case-control study in Stockholm County, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

46,366 cases of incident myocardial infarction and stratified controls |

Foreign-born subjects had a higher incidence of myocardial infarction than those born in Sweden (RR for men = 1.17, 95% CI 1.13, 1.21; RR for women = 1.15, 95% CI 1.09, 1.21). An increased incidence was present primarily in subjects born in Finland, other Nordic countries, Poland, Turkey, Syria and South Asia in both genders, from the Netherlands among men, and from Iraq among women. |

|

Hedlund et al., (2008) |

Population-based cohort study in Stockholm, Sweden |

Total mortality |

Incident cases of myocardial infarction |

After adjustment for socioeconomic status, male immigrants had a lower mortality within 28 days after a first myocardial infarction compared to Sweden-born (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.76, 0.94). Among women, there was a weak similar relationship (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.76, 1.10). There were no important differences between foreign-born and Sweden-born in 1-year mortality. |

|

Saposnik et al.,(2010) |

Population-bases, matched, retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada |

Hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk for myocardial infarction |

The incidence rate of acute myocardial infarction was 4.14 per 10,000 persons among new immigrants and 6.61 per 10,000 person-years among long-term residents (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.63, 0.69). |

|

Hempler et al., (2011) |

Registry-based follow-up study in Denmark |

Incident acute myocardial infarction |

Persons at risk of acute myocardial infarction |

Immigrant men and women from Turkey and Pakistan had an increased incidence of acute myocardial infarction. No notable differences were observed between former Yugoslavians and native Danes. |

|

Deckert et al., (2013) |

Retrospective cohort study in Germany |

Total mortality and acute myocardial infarction incidence

|

Persons at risk for acute myocardial infarction |

Acute myocardial infarction incidence was higher in male repatriates (standardized incidence ratio = 1.30, 95% CI 1.02, 1.65) than in the general German population. |

|

van Oeffelen et al., (2014) |

Population-based cohort study in The Netherlands |

Acute myocardial infarction and total mortality

|

Persons hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Mortality and acute myocardial infarction readmission rates were higher among immigrants as compared with ethnic Dutch. |

|

Dzayee et al.., (2014) |

Nationwide cohort study in Sweden |

Recurrent myocardial infarction |

518,503 patients diagnosed with first myocardial infarction |

Foreign-born men and women had a slightly increased HR than Sweden-born men and women. Foreign-born who had lived in Sweden for less than 35 years had a higher risk than those who had lived there for 35 years or longer. |

|

Shvartsur et al., (2018) |

Retrspective cohort study in Israel |

Total mortality |

11,143 Israeli-born and immigrant acute myocardial infarction patients |

10-year mortality rates were 65% lower in Israeli-born patients compared with immigrants. |

Table 3: Studies of social support and myocardial infarction risk and survival.

|

Author |

Design |

Outcomes |

Sample |

Results |

|

Berkman et al., (1992) |

Cohort study in New Haven, CT |

Total mortality |

194 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Lack of emotional support was significantly associated with mortality (OR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.2, 6.9). |

|

Jenkinson et al., (1993)

|

Cohort study in England |

Total mortality |

1,376 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Socially isolated patients were 49% more likely to die after an infarction than patients who were not socially isolated. |

|

Friedmann & Thomas, (1995) |

Follow-up study of randomized controlled trial participants |

Total mortality |

368 myocardial infarction patients |

High social support tended to predict survival independently of demographic and other psychosocial variables (p<0.068). |

|

Greenwood et al., (1995) |

Cohort study in England |

Total mortality |

1,701 patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Lack of social contacts or being unmarried were not significantly associated with survival. |

|

Farmer et al., (1996) |

Cohort study in Corpus Christi, TX |

Total mortality |

596 patients with myocardial infarction |

Survival following myocardial infarction was greater for those with high or medium social support than for those with low social support. The RR of mortality was 1.89 (95% CI 1.20, 2.97) for those with low social support. |

|

Hammer et al., (1998) |

Population-based case-control study in five Swedish counties |

Incident myocardial infarction |

Men and women in five counties in Sweden who were at risk of myocardial infarction |

Younger men (30-54 years of age) in occupations with both high job strain and low social support at work had a RR of 1.79 (95% CI 1.22, 2.65) compared with subjects in low strain and high social support jobs. |

|

Pederson et al., (2004) |

Follow-up study of patients 4-6 weeks post- myocardial infarction and at 9 months |

Recurrent cardiac events |

112 myocardial infarction patients treated at two hospitals in Denmark |

Lower social support at baseline was associated with an increased risk of recurrent cardiac events at follow-up (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.84, 0.97). |

|

Andre-Petersson et al., (2006) |

Cohort study of men in Malmo, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction and total mortality |

Men born in Malmo, Sweden who were at-risk of myocardial infarction |

Low levels of social support was associated with an increased risk of incident myocardial infarction (HR = 2.40, 95% CI 1.36, 4.25, p = 0.003) and premature death (HR = 1.99, 95% CI 1.32, 3.00, p = 0.001). |

|

Schmaltz et al., (2007) |

Study of all patients discharged with a primary diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction from three medical centers in Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

Mortality |

Patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Living alone was independently associated with mortality (adjusted HR = 1.6, 95% CI 1.0, 2.5), but interacted with patient sex. Men living alone had the highest mortality risk (HR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.1, 3.7), followed by women living alone, men living with others, and women living with others. |

|

Chaix et al., (2006) |

Cohort study of men in Malmo, Sweden |

Acute myocardial infarction and death due to chronic IHD |

498 men at risk of acute myocardial infarction or death due to IHD |

Low neighborhood-based social support was associated with increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and IHD mortality. The hazard ratios for IHD death associated with neighborhood social support were 2.50 (95% CI 1.06, 5.91) in the lower tertile and 1.66 (95% CI 0.70, 3.93) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile. The hazard ratios for incident myocardial infarction associated with neighborhood social support were 1.87 (95% CI 1.02, 3.43) in the lower tertile and 1.60 (95% CI 0.89, 2.86) in the middle tertile compared with the upper tertile. |

|

Andre-Petersson et al., (2007) |

Cohort study in Malmo, Sweden |

Incident myocardial infarction |

7,770 men and women at risk of myocardial infarction |

Among women, low levels of social support at work was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. No association was observed among men. |

|

Lett et al., (2007) |

Prospective study of randomized controlled trial participants |

Total mortality and non-fatal reinfarction |

1,481 acute myocardial infarction patients |

Higher levels of perceived social support were associated with improved outcome for patients without elevated depression but not for patients with high levels of depression. The relation between perceived social support and mortality or nonfatal infarction did not reach statistical significance. |

|

Nielsen & Mard, (2010) |

Cohort study in Denmark |

Total mortality |

242 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Single living was an independent predictor of death (HR = 2.55, 95% CI 1.52, 4.30). |

|

Bucholz et al., (2011) |

Registry-based cohort study at 19 U.S. medical centers |

Acute myocardial infarction and 4-year mortality |

Patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction |

Patients who lived alone had a comparable risk of mortality (HR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.76, 1.28) as patients who lived with others. |

|

Kitamura et al., (2013) |

Cohort study in Osaka region of Japan |

Major adverse cardiovascular events and total mortality |

5,845 patients with acute myocardial infarction |

Living alone was associated with a higher risk of composite endpoint consisting of major adverse cardiovascular events and total deaths (HR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.11, 1.58). |

|

Gafarov et al., (2013) |

Cohort study |

Incident myocardial infarction |

870 women in Novosibirsk, Russia |

The rate of myocardial infarction was higher in married women with fewer close contacts and smaller social networks. |

|

Quinones et al., (2014) |

Registry-based cohort study in Augsburg, Germany |

Total mortality |

3,766 patients with incident myocardial infarction |

Overall, marital status showed a statistically non-significant inverse association (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.47, 1.22). Stratified analyses revealed strong protective effects only among men and women aged < 60 years who were diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. |

|

Kilpi et al., (2015) |

Population-based cohort study in Finland |

Myocardial infarction incidence and mortality |

302,885 persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

Men who were married had a lower risk of myocardial infarction as compared with those who were unmarried, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors. Among women, the associations of living arrangements with myocardial infarction were explained by socioeconomic factors. Living arrangements were strong predictors of survival after myocardial infarction. |

|

Weiss-Faratci et al., (2016) |

Cohort study in Israel |

Total mortality at two time points |

Patients with incident myocardial infarction |

Higher perceived social support was associated with lower mortality at both time points (HR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.75, 0.96; HR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.66, 0.83, respectively). |

|

Hakulinen et al., (2018) |

Cohort study in the United Kingdom |

Incident acute myocardial infarction and total mortality |

479,054 persons at risk of myocardial infarction |

Social isolation was associated with higher risk of acute myocardial infarction (HR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.3-1.55). |

References

- Sean A Coady, Norman J Johnson, Jahn K Hakes, Paul D Sorlie (2014) Individual education, area income, and mortality and recurrence of myocardial infarction in a Medicare cohort: the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. BMC Public Health 14: 705. [Crossref]

- V Salomaa, H Miettinen, M Niemelä, M Ketonen, M Mähönen et al. (2001) Relation of socioeconomic position to the case fatality, prognosis and treatment of myocardial infarction evens; the FINMONICA MI Register Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 55: 475-482. [Crossref]

- Emily M Bucholz, Shuangge Ma, Sharon Lise T Normand, Harlan M Krumholz (2015) Race, socioeconomic status, and life expectancy after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 132: 1338-1346. [Crossref]

- Fanny Kilpi, Karri Silventoinen, Hanna Konttinen, Pekka Martikainen (2015) Disentangling the relative importance of different socioeconomic resources for myocardial infarction incidence and survival: a longitudinal study of over 300,000 Finnish adults. Eur J Public Health 26: 260-266. [Crossref]

- Ninoa Malki, Ilona Koupil, Sandra Eloranta, Caroline E Weibull, Sanna Tiikkaja et al. (2014) Temporal trends in incidence of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke by socioeconomic position in Sweden 1987-2010. PLoS One 9: e105279. [Crossref]

- David A Alter, Alice Chong, Peter C Austin, Cameron Mustard, Karey Iron et al. (2006) Socioeconomic status and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 144: 82-93. [Crossref]

- Anna M Kucharska Newton, Kennet Harald, Wayne D Rosamond, Kathryn M Rose, Thomas D Rea et al. (2011) Socioeconomic indicators and the risk of acute coronary heart disease events: comparison of population-based data from the United States and Finland. Ann Epidemiol 21: 572-579. [Crossref]

- G D Smith, J D Neaton, D Wentworth, R Stamler, J Stamler (1996) Socioeconomic differentials in mortality risk among men screened for the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial: I. white men. Am J Public Health 86: 486-496. [Crossref]

- G D Smith, D Wentworth, J D Neaton, R Stamler, J Stamler (1996) Socioeconomic differentials in mortality risk among men screened for the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial: I. Black men. Am J Public Health 86: 497-504. [Crossref]

- J E Ferrie, P Martikainen, M J Shipley, M G Marmot (2005) Self-reported economic difficulties and coronary events in men: evidence from the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol 34: 640-648. [Crossref]

- Maria Rosvall, Sofia Gerward, Gunnar Engström, Bo Hedblad (2008) Income and short-term case fatality after myocardial infarction in the whole middle-aged population of Malmo, Sweden. Eur J Public Health 18: 533-538. [Crossref]

- Iain A Lang, David J Llewellyn, Kenneth M Langa, Robert B Wallace, Felicia A Huppert et al. (2008) Neighborhood deprivation, individual socioeconomic status, and cognitive function in older people: analyses from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Am Geriatrics Soc 56: 191-198. [Crossref]

- Farouk Mookadam, Heather M Arthur (2004) Social support and its relationship to morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview. Arch Int Med 164: 1514-1518. [Crossref]

- D A Alter, C D Naylor, P Austin, J V Tu (1999) Effects of socioeconomic status on access to invasive cardiac procedures and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 341: 1359-1367. [Crossref]

- Maria K Stjärne, Antonio Ponce de Leon, Johan Hallqvist (2004) Contextual effects of social fragmentation and material deprivation on risk of myocardial infarction—results from the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. Int J Epidemiol 33: 732-741. [Crossref]

- Maria K Stjärne, Johan Fritzell, Antonio Ponce De Leon, Johan Hallqvist, SHEEP Study Group (2006) Neighborhood socioeconomic context, individual income and myocardial infarction. Epidemiology 17: 14-23. [Crossref]

- Basile Chaix, Maria Rosvall, Juan Merlo (2007) Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and residential instability: effects on incidence of ischemic heart disease and survival after myocardial infarction. Epidemiology 18: 104-111. [Crossref]

- John R Beard, Arul Earnest, Geoff Morgan, Hsien Chan, Richard Summerhayes et al. (2008) Socioeconomic disadvantage and acute coronary events. A spatiotemporal analysis. Epidemiology 19: 485-492. [Crossref]

- Kathryn M Rose, Chirayath M Suchindran, Randi E Foraker, Eric A Whitsel, Wayne D Rosamond et al. (2009) Neighborhood disparities in incident hospitalized myocardial infarction in four U.S. communities: the ARIC Surveillance Study. Ann Epidemiol 19: 867-874. [Crossref]

- Carolyn A Davies, Ruth Dundas, Alastair H Leyland (2009) Increasing socioeconomic inequalities in first acute myocardial infarction in Scotland, 1990-92 and 2000-02. BMC Public Health 9: 134. [Crossref]

- Yariv Gerber, Yael Benyamini, Uri Goldbourt, Yaacov Drory, Israel Study Group on First Acute Myocardial Infarction (2010) Neighborhood socioeconomic context and long-term survival after myocardial infarction. Circulation 121: 375-383. [Crossref]

- Göran Henriksson, Gunilla Ringbäck Weitoft, Peter Allebeck (2010) Associations between income inequality at municipality level and health depend on context-a multilevel analysis on myocardial infarction in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 71: 1141-1149. [Crossref]

- Séverine Deguen, Benoît Lalloue, Denis Bard, Sabrina Havard, Dominique Arveiler et al. (2010) A small-area ecologic study of myocardial infarction, neighborhood deprivation, and sex. A Bayesian modeling approach. Epidemiology 21: 459-466. [Crossref]

- Claudia Blais, Denis Hamel, Stéphane Rinfret (2012) Impact of socioeconomic deprivation and area of residence on access to coronary revascularization and mortality after a first acute myocardial infarction in Quebec. Can J Cardiol 28: 169-177. [Crossref]

- Avshalom Koren, David M Steinberg, Yaacov Drory, Yariv Gerber, Israel Study Group on First Acute Myocardial Infarction et al. (2012) Socioeconomic environment and recurrent coronary events after initial myocardial infarction. Ann Epidemiol 22: 541-546. [Crossref]

- Carla Koopman, Aloysia AM van Oeffelen, Michiel L Bots, Peter M Engelfriet, WM Monique Verschuren et al. (2012) Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in incidence of acute myocardial infarction: a cohort study quantifying age- and gender-specific differences in relative and absolute terms. BMC Public Health 12: 617. [Crossref]

- Jeong Hun Kim, Myung Ho Jeong, In Hyae Park, Jin Soo Choi, Jung Ae Rhee et al. (2014) The association of socioeconomic status with three-year clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. J Korean Med Sci 29: 536-543. [Crossref]

- Kymberley Thorne, John G Williams, Ashley Akbari, Stephen E Roberts (2015) The impact of social deprivation on mortality following acute myocardial infarction, stroke or subarachnoid haemorrhage: a record linkage study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 15: 71. [Crossref]

- Daniel Kim, Richard H Glazier, Brandon Zagorski, Ichiro Kawachi, Philip Oreopoulos (2018) Neighborhood socioeconomic position and risks of major chronic diseases and all-cause mortality: a quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open 8: e018793. [Crossref]

- L Alfredsson, A Ahlbom, T Theorell (1982) Incidence of myocardial infarction among male Finnish immigrants in relation to length of stay in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol 11: 225-228. [Crossref]

- Ebba Hedlund, Anders Lange, Niklas Hammar (2007) Acute myocardial infarction incidence in immigrants to Sweden. Country of birth, time since immigration, and time trends over 20 years. Eur J Epidemiol 22: 493-503. [Crossref]

- Ebba Hedlund, Kenneth Pehrsson, Anders Lange, Niklas Hammar (2008) Country of birth and survival after a first myocardial infarction in Stockholm, Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol 23: 341-347. [Crossref]

- G Saposnik, D A Redelmeier, H Lu, E Fuller Thomson, E Lonn et al. (2010) Myocardial infarction associated with recency of immigration to Ontario. QJM 103: 253-258. [Crossref]

- Nana F Hempler, Finn B Larsen, Signe S Nielsen, Finn Diderichsen, Anne H Andreasen et al. (2011) A registry-based follow-up study, comparing the incidence of cardiovascular disease in native Danes and immigrants born in Turkey, Pakistan and the former Yugoslavia: do social inequalities play a role? BMC Public Health 11: 662. [Crossref]

- Andreas Deckert, Volker Winkler, Christa Meisinger, Margit Heier, Heiko Becher (2013) Myocardial infarction incidence and ischemic heart disease mortality: overall and trend results in repatriates, Germany. Eur J Public Health 24: 127-133. [Crossref]

- A A M van Oeffelen, C Agyemang, K Stronks, M L Bots, I Vaartjes et al. (2014) Prognosis after a first hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure by country of birth. Heart 100: 1436-1443. [Crossref]

- Dashti Ali M Dzayee, Omid Beiki, Rickard Ljung, Tahereh Moradi (2014) Downward trend in the risk of second myocardial infarction in Sweden, 1987-2007: breakdown by socioeconomic position, gender, and country of birth. Eur J Prev Cardiol 21: 549-558. [Crossref]

- Rachel Shvartsur, Arthur Shiyovich, Harel Gilutz, Abed N Azab, Ygal Plakht et al. (2018) Short and long-term prognosis following acute myocardial infarction according to the country of origin. Soroka acute myocardial infartcion II (SAM II) project. Int J Cardiol 259: 227-233. [Crossref]

- L F Berkman, L Leo Summers, R I Horwitz (1992) Emotional support and survival after myocardial infarction. A prospective, population-based study of the elderly. Ann Intern Med 117: 1003-1009. [Crossref]

- C M Jenkinson, R J Madeley, J R Mitchell, I D Turner (1993) The influence of psychosocial factors on survival after myocardial infarction. Public Health 107: 305-317. [Crossref]

- E Friedmann, S A Thomas (1995) Pet ownership, social support, and one-year survival after acute myocardial infarction in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). Am J Cardiol 76: 1213-1217. [Crossref]

- D Greenwood, C Packham, K Muir, R Madeley (1995) How do economic status and social support influence survival after initial recovery from acute myocardial infarction? Soc Sci Med 40: 639-647. [Crossref]

- I P Farmer, P S Meyer, D J Ramsey, D C Goff, M L Wear et al. Higher levels of social support predict greater survival following acute myocardial infarction: the Corpus Christi Heart Project. Behav Med 22: 59-66. [Crossref]

- N Hammar, L Alfredsson, J V Johnson (1998) Job strain, social support at work, and incidence of myocardial infarction. Occup Environ Med 55: 548-553. [Crossref]

- Susanne Schmidt Pedersen, Ron Theodoor van Domburg, Mogens Lytken Larsen (2004) The effect of low social support on short-term prognosis in patients following a first myocardial infarction. Scan J Psychol 45: 313-318. [Crossref]

- Lena André Petersson, Bo Hedblad, Lars Janzon, Per Olof Ostergren (2006) Social support and behavior in a stressful situation in relation to myocardial infarction and mortality: who is at risk? Results from prospective cohort study “Men Born in 1914,” Malmo, Sweden. Int J Behav Med 13: 340-347. [Crossref]

- Heidi N Schmaltz, Danielle Southern, William A Ghali, Susan E Jelinski, Gerry A Parsons et al. (2007) Living alone, patient sex and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Int Med 22: 572-578. [Crossref]

- Basile Chaix, Maria Rosvall, Juan Merlo (2006) Recent increase of neighborhood socioeconomic effects on ischemic heart disease mortality: a multilevel survival analysis of two large Swedish cohorts. Am J Epidemiol 165: 22-26. [Crossref]

- Lena André Petersson, Gunnar Engström, Bo Hedblad, Lars Janzon, Maria Rosvall (2007) Social support at work and the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in women and men. Soc Sci Med 64: 830-841. [Crossref]