Pneumorrhachis: A Rare Prognostic Lesson

A B S T R A C T

Objective: We present a case of poly-traumatic epidural pneumorrhachis of an 87-year-old gentleman who had unremarkable neurology on presentation. We give an overview of aetiology and indications for intervention in pneumorrhachis.

Background: Pneumorrhachis is the presence of air within the spinal canal, aetiologically it is widely variable though its observation in practice is rare.

Methods: Descriptive.

Results: We show figures illustrating CT images of pneumorrhachis at C3/4 level. The patient underwent progressive neurological deterioration over the course of four days on intensive care, and subsequently passed away.

Conclusion: The presence of pneumorrhachis is well known to be associated with poor prognosis, and in our case predicted his subsequent neurological decline despite initial presentation. The presence of pneumorrhachis also serves as an important clue for hidden injuries.

Keywords

Pneumorrhachis, trauma, prognostication

Introduction

Pneumorrhachis is a rare radiological finding where air is present within the spinal canal. Pneumorrhachis can be subdivided into extradural or intradural, intradural air is often associated with more severe trauma and pneumocephalus [1]. Mechanisms by which pneumorrachis can occur are categorized into traumatic, non-traumatic and iatrogenic. Patients mostly presents as asymptomatic, but may have pain, neurological deficits, or symptoms of intracranial or intraspinal hypertension [2].

Case Presentation

We present a case of epidural pneumorrhachis following trauma. Patient is an 87-year-old man with good functional baseline and no significant past medical history. The patient self-presented to the local hospital with confusion, retrograde amnesia, hypothermia and metabolic acidosis. Initial neurology on presentation: GCS 14, bilateral down-going plantars, moving all four limbs.

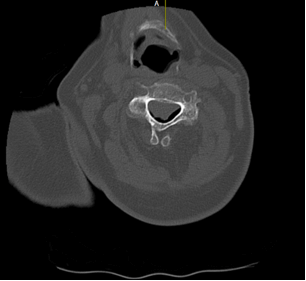

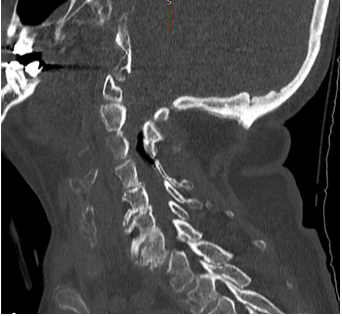

A CT was performed at the local hospital which showed pneumorrhachis at C3/4 level (see Figures 1-3), alongside multiple fractures and injuries of the thorax. The patient was then transferred under the care of spinal team to intensive care.

Figure 1: Axial CT scan through C-spine demonstrating pneumorrhachis.

Figure 2: Coronal CT scan through C-spine demonstrating pneumorrhachis.

Figure 3: Sagittal CT scan through C-spine demonstrating pneumorrhachis.

Subsequent bloods showed acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, significant electrolyte disturbance and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Initial trauma CT showed C3/4 pneumorrhachis, unstable T8/9 fracture, sternal fracture, bilateral scapular fractures, bilateral pleural effusions and rib fractures with flail segment. Air was seen in the anterior mediastinum tracking to T8/9 disc space, and within the spinal canal at C3/4 level. MRI revealed unstable T8/9 fracture through the disc space and an epidural haematoma with no cord compression, the patient was listed for spinal fixation. The mechanism of trauma is not known. Next evening, patient’s GCS had decreased to 12, power 4/5 all four limbs. A do-not- resuscitate form was put in place due to the severity of his injuries. On the fourth day after presentation, patient dropped his GCS to three, then passed away hours later.

Discussion

The most likely explanation for his decreased GCS is metabolic disturbance secondary to his trauma, and subsequent multi-organ failure caused by systemic inflammatory response. Intracranial injury was ruled out by three consecutive CTs. However, it is plausible the collection of extradural air extended or mobilized into pneumocephalus, causing intracranial hypertension. A CT was not performed on the last day. The patient also suffered progressive respiratory failure, for which pneumorrhachis itself at C3/4 level could have contributed through compression of nerve roots supplying the diaphragm. Air entrance in this case is likely through the sternal fracture and fractured thoracic disc space.

The first case of pneumorrhachis was first described in 1977 by Gordon et al. [3]. Of traumatic causes, pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum are the most common causes. Of non-traumatic causes, numerous aetiologies include spontaneous pneumothoraces, pneumomediastinum from bronchiolitis, spontaneous surgical emphysema (Hamman syndrome), cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Some of the more intriguing causes include violent coughing or sneezing, regional necrotizing fasciitis, thoraco-arachnoid fistulas, foreign body inhalation, and post-radiotherapy changes [4-12]. Pneumorrhachis is usually managed conservatively, in cases where there is evidence of increased intraspinal or intracranial pressure, surgical decompression can be considered.

There have also been reported cases of use of IV dexamethasone, epidural air aspiration, trephination and oxygen therapy for treatment of pneumorrhachis [13-16]. The anaesthetist should be made aware of the presence of air, due to dangers of nitric oxide migrating into the spinal canal. CT is the imaging modality of choice as air is seen as marked contrast to CSF and the spinal cord [17]. Mostly the air is distributed in cervical and thoracic spine, as opposed to the lumbosacral spine, although largely positional. Skull trauma also often push air into the cervical canal due to head up and supine position of the patient. Air is more frequently present in the posterior canal, as soft tissue here are more loosely connected compared to the anterior canal.

We urge readers to remember the important prognostic lesson pneumorrhachis serves, as demonstrated by our case. It is also crucial to screen for concomitant hidden injuries whenever pneumorrhachis is seen and intervene when neurological signs of intracranial or intraspinal pressure is present.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Article Info

Article Type

Case ReportPublication history

Received: Sat 04, Sep 2021Accepted: Fri 24, Dec 2021

Published: Thu 30, Dec 2021

Copyright

© 2023 Rosa Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.SCR.2021.12.03

Author Info

Corresponding Author

Rosa SunDepartment of Neurosurgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, UK

Figures & Tables

References

1. Oertel MF, Korinth

MC, Reinges MHT, Krings T, Terbeck S et al. (2006) Pathogenesis, diagnosis and

management of pneumorrhachis. Eur Spine J 15: 636-643. [Crossref]

2. Thakur S, Kumar S,

Sharma S, Thakur CS (2016) Mystery Case: Pneumorrhachis: A radiographic

diagnosis. Neurology 86: e134-e135. [Crossref]

3. Gordon IJ, Hardman

DR (1977) The traumatic pneumomyelogram. A previously undescribed entity. Neuroradiology

13: 107-108. [Crossref]

4. Aribas OK, Gormus

N, Aydogdu KD (2001) Epidural emphysema associated with primary spontaneous

pneumothorax. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20: 645-646. [Crossref]

5. Tsuji H, Takazakura E, Terada Y, Makino H, Yasuda A et al. (1989) CT

demonstration of spinal epidural emphysema complicating bronchial asthma and

violent coughing. J Comput Assist Tomogr 13: 38-39. [Crossref]

6. Krishnan P, Das S,

Chandramouli B (2017) Epidural pneumorrhachis consequent to Hamman syndrome. J

Neurosci Rural Pract 8: 118-119. [Crossref]

7. Pedicelli G, Santis

M, Mattia P (1997) Pneumorachis following asthma-induced barotrauma CT

recognition of an unusual manifestation of life-threatening asthma. Eur

Radiol 7: S100.

8. Chiba Y, Kakuta H

(1995) Massive subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and spinal epidural

emphysema as complications of violent coughing: a case report. Auris Nasus

Larynx 22: 205-208. [Crossref]

9. Spock CR, Roberto

AM, Rahul VS, Grauer JN (2006) Necrotizing infection of the spine. Spine

(Phila Pa 1976) 31: E342-E344. [Crossref]

10. Lee GS, Lee MK, Kim

WJ, Kim HS, Kim JH et al. (2016) Pneumocephalus and Pneumorrhachis due to a

Subarachnoid Pleural Fistula That Developed after Thoracic Spine Surgery. Korean

J Spine 13: 164-166. [Crossref]

11. Bernaerts A,

Verniest T, Vanhoenacker F, den Brande PV, Petré C et al. (2003) Pneumomediastinum

and epidural pneumatosis after inhalation of “Ecstasy”. Eur Radiol 13:

642-643. [Crossref]

12. Ristagno RL,

Hiratzka LF, Rost Jr RC (2002) An unusual case of pneumorrhachis following

resection of lung carcinoma. Chest 121: 1712-1714. [Crossref]

13. Nay PG,

Milaszkiewicz R, Jothilingam S (1993) Extradural air as a cause of paraplegia

following lumbar analgesia. Anaesthesia 48: 402-404. [Crossref]

14. Kennedy TM, Ullman

DA, Harte FA, Saberski LR, Greenhouse BB (1988) Lumbar root compression

secondary to epidural air. Anesth Analg 67: 1184-1186. [Crossref]

15. Paik NC, Lim CS,

Jang HS (2013) Cauda equina syndrome caused by epidural pneumorrhachis:

treatment with percutaneous computed tomography- guided translaminar

trephination. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38: E440-E443. [Crossref]

16. Hazouard E, Koninck JC, Attucci S, Fauchier-Rolland F, Brunereau L et al. (2001) Pneumorachis and pneumomediastinum caused by repeated Müller`s maneuvers: complications of marijuana smoking. Ann Emerg Med 38: 694-697. [Crossref]

17. Singh J, Kharosekar H, Velho V (2013) Post-operative intradural tension pneumorrhachis. Neurol India 61: 664-665. [Crossref]