A One-Year Audit of Varicose Vein Surgery at a Vascular Surgical Unit with a Long-Term Duplex and Quality of Life Follow-Up

A B S T R A C T

Objective: With the introduction of endovenous treatments, open varicose veins surgery was discarded due to a claimed high risk of neovascularisation. A one-year audit was set up to look at results from performing mainly open surgery.

Methods: All varicose vein interventions were registered and prospectively followed with colour Duplex assessments after 4-6 weeks, 1 and >5 years. In addition, Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire (AVVQ) was used in addition to Varicose Vein Severity Score (VCSS) to assess patients’ quality of life (QoL) and the disease severity.

Results: During the year, 236 patients/252 legs were operated and 28% were re-do procedures. Median age was 55 years (16-87) and 70% were females. Duplex at 4-6 weeks showed a primary success rate of 91%. Neovascularisation was noted in 8% one year after primary surgery. The long-term assessment was done after a median of 69 months (39-75) and 67% of all legs were examined. After primary surgery 16% showed neovascularisation compared with and 27% after re-do procedures. VCSS improved significantly from 6 (range 1-22) to 2 at the long-term follow-up (p<0.001). The AVVQ score improved from 20 (range 3-55) down to 10 (p<0.001).

Conclusion: The risk for neovascularisation seems to have been overestimated and good long-term results can be achieved following modern open surgery. The major problem is to avoid varicose vein recurrence since results from re-do procedures seem less favourable long term.

Keywords

Varicose veins, varicose vein surgery, varicose vein recurrence, audit, quality of life

Introduction

Although high ligation and stripping of incompetent saphenous veins have been used for more than 100 years the modern results from such interventions have not been studied in detail. The technique of open varicose vein surgery has been improved over time and has become more minimal invasive just as all endovenous alternatives that have been introduced. Following the introduction of endovenous interventions multiple randomized controlled studies appeared comparing the new endovenous treatments with open surgery consisting of high ligation and stripping. The patients in RCTs are highly selected and usually not always representative of varicose vein patients in general. Recurrence rates, in some of these studies, were reported astonishingly high for open surgery, approaching 20% groin recurrence already within one year [1, 2]. This high risk of early recurrence and especially neovascularization was not recognized from our clinical everyday work [3]. Traditionally correct open surgery, including ligation of groin tributaries and performing a true high ligation avoiding remaining stumps at the sapheno-femoral junction (SFJ), has been considered mandatory to minimize recurrence. Further, the clinical importance of neovascularization has been questioned [4]. In addition, a high proportion of the routine venous interventions regards recurrent disease that has not previously been sufficiently studied. By using an adequate surgical technique, a lot of early recurrences ought to be avoided. It was felt that an audit was appropriate to ascertain what results could be expected in routine clinical practice from mainly open varicose vein surgery, both regarding primary and recurrent disease.

The aim of this audit was to document the clinical result from all types of venous interventions performed at our vascular surgical unit to ascertain the quality of the treatments given before starting to use endovenous alternatives. The results were analysed both from the patient’s perspective (health related quality of life) as well as the caregiver’s perspective (effect on disease severity).

Methods

This was a prospective audit including all varicose vein surgery performed at our vascular surgical unit during a 12-month period, from September 1st, 2009, until August 31st, 2010, followed by a long-term follow-up (> 5 years). All patients who had surgery during this period were offered this more extensive follow-up. Since it was an audit no formal ethical approval was necessary at that time, but the audit was approved by the hospital and informed consent was sought from all patients. Patients could withdraw their consent to follow-up at any time. The data were analysed at group level making it impossible to identify any individual patients. All patients that underwent varicose vein interventions at Skaraborg Hospitals in Skövde or Falköping (day surgery center) were included, representing a catchment area of approximately 200 000 people, and in addition around 10 percent were referred from other parts of Sweden.

I Pre-Operative Assessments

All patients had a colour Doppler ultrasound (CDU) scan performed pre-operatively to monitor the venous incompetence in the leg. All duplex assessments were done by vascular technologists at the accredited vascular laboratory in Skövde. Patients were examined standing on a tilting table. Pneumatic compression of the calf was used to achieve standardized proximal venous blood flow. Significant incompetence was considered present if the reflux exceeded 0.5 second. Only patients with symptomatic venous incompetence were considered for intervention. Patients were classified according to the CEAP venous clinical grading system, and the venous clinical severity score (VCSS) was assessed directly pre-operatively by the surgeon. Patients also completed the Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire (AVVQ: a disease related quality of life tool) before the intervention.

II Post-Operative Assessments

Immediately after performing surgery, the surgeon filled in a questionnaire with details regarding the type of surgery performed, differentiating between primary and re-do surgery. A duplex scanning was performed after 4-6 weeks to document the early result, performed by a vascular technologist and never by the surgeon to avoid evaluation bias. Primary success was deemed achieved if there were no remaining refluxing veins left at the surgical site and no signs of technical errors. At that visit any complications during the early post-operative period were asked for and noted.

III Short Term Follow-Up

After 12 months patients living in Skaraborg County were invited for an additional full venous CDU scanning at the vascular laboratory in Skaraborg Hospital Skövde. The result regarding the success in correcting pre-operative venous incompetence was scored in a duplex assessment protocol. Special notice was spent on detecting saphenous stumps and neovascularization in the groin that the vascular technologists had received special training to be able to detect and to grade (Grade 1 or 2) [5, 6]. The patients were also asked to once again answer the disease specific QoL instrument AVVQ. The VCSS protocol was filled in by the vascular technologist performing the duplex scanning, who had received training in filling out this protocol and considered to be an objective assessor to avoid bias.

IV Long Term Follow-Up

The long-term follow-up was planned after 5 years and consisted of a full venous CDU scanning, AVVQ assessment and VCSS performed just as at the 12 months follow-up. The long-term follow-up was restricted to patients living in Skaraborg County. In addition to evaluating Disease specific QoL and disease severity, patients were asked about their satisfaction regarding symptom relief, cosmetic result, and the overall result, according to validated questions used in a previous study [3].

V Statistics

Continuous variables were given as median (range) if not normally distributed. Median values regarding repeated measurements of AVVQ and VCSS were examined using the Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing AVVQ and VCSS scores for patients with and without residual incompetent lower leg GSVs. A significant result was considered if the p value was < 0.05.

Results

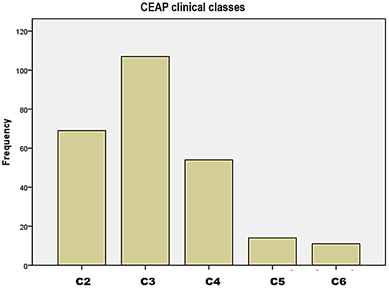

For twelve months 232 patients had interventions performed for varicose veins in 252 legs, representing 125 interventions/100 000 population and year and 90/100 000 if excluding patients from outside our own catchment area. The median age was 55 years (range 16-87), and 70% women. Around 10% were referred from other Counties and 91% were performed as day surgery cases. Altogether more than ten surgeons were involved but the great majority of operations were performed by four vascular surgeons. The venous clinical grading according to CEAP is shown in (Figure 1), with C3 patients dominating.

Figure 1: CEAP clinical class for all patients entering the audit.

I Interventions Performed

Primary surgery was performed in 72% (183/252) and the rest (69) had re-do procedures. The majority (83%) regarded Great saphenous vein (GSV) surgery, 12 had simultaneous SSV surgery and 25 had only SSV surgery. The median diameter of the GSV, measured 3 cm distally to the sapheno-femoral junction (SFJ), was 9,5 mm for primary surgery cases and for primary Short saphenous vein (SSV) surgery the median diameter was 7.3 mm. Only five interventions were endovenous laser treatments and the rest open venous surgery. 151 had primary GSV surgery and 33 (13%) had re-do groin surgery because of recurrence due to retained saphenous stumps. Re-do surgery took in median 7 minutes longer to perform, 55 vs. 48 minutes (p< 0.005). The surgery was combined with stab avulsions in 81% of the procedures. The stripper used had a second option to cone-strip, via a guide wire in the vein, if it snapped during invagination stripping.

II Outcomes 30 Days

Complications occurred in 8% and were mostly mild. More severe pain was most common 2.8%, followed by wound infection in 2%, thrombophlebitis or haematoma in 1.6%, severe swelling in 1.2% and one case with a sensory nerve injury and one patient developed a deep vein thrombosis (0.4% each). A post-operative CDU scan was performed of 239/252 legs (95%). The performed surgery was judged complete in 230 legs (91%), with no remaining incompetence at the site of intervention. There was minor remaining incompetence in 6 legs and 3 legs showed technical failures.

III One-Year Follow-Up

A CDU scan was performed in 232/252 legs (92%). No remaining venous incompetence was detected in 199 legs (86%). There were some incompetent veins detected in 33 legs (14%). For patients who had primary GSV surgery CDU was repeated in 138/151 legs (91%). 115/138 showed no groin recurrences (neovascularization) or residual incompetent veins. The outcome of the repeat CDU scanning is summarized in (Table 1). For legs having had re-do groin surgery more neovascularization was noted (13%) and stumps in 10%.

Table 1: Outcome from vein CDU scanning of 232/252 legs (92%)

after 12 months.

|

Overall outcome |

Number of legs |

% |

|

No remaining incompetence |

199 |

86 |

|

Some incompetence detected |

33 |

14 |

|

Primary groin surgery (All primary) |

137 (167) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

11 |

8 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

6** (+5 without incompetence#) |

8 |

|

Re-do groin surgery (All re-do) |

30 (65) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

4 |

13 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

3 |

10 |

|

Primary SSV* surgery |

34 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

4 |

12 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

2 |

6 |

|

Re-do SSV* surgery |

14 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

2 |

14 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

2 |

14 |

#3 stumps after laser ablation and 2

following open surgery **1 after laser.

IV Long Term Follow-Up

The long-term follow-up was undertaken after a median of 69 months (range 39-79). Reasons for not attending the long-term follow-up are shown in (Table 2). A CDU scan was performed in 172/252 legs (68%). No remaining incompetence was found in 120 legs (70%) and there was some incompetence detected for the remaining 52 legs. The long-term CDU scan was performed in 101/151 legs treated with primary GSV groin surgery. The outcome of the CDU scanning is shown in (Table 3). For legs treated with re-do groin surgery 27% had neovascularization and 18% showed saphenous stumps. At the long-term follow-up neutral observers noted visible varicosities in 64% of the legs; few in 53%, multiple in 10% and extensive in 1%, according to the VCSS protocol.

Table

2:

Reasons for not attending the full long-term follow-up.

|

Reasons |

Number of patients |

|

Living in other counties |

27 |

|

High age or bad health |

6* |

|

Deceased |

9 |

|

Declined follow-up. |

12# |

|

Unknown reason |

30 |

|

Repeat surgery due to new/residual incompetence |

5** |

*1

declined CDU but responded to questionnaires.

#6

declined the CDU but responded to questionnaires.

**3

followed until re-do surgery and one full time after clearing a residual

incompetent perforator.

Table

3:

Outcome from vein CDU scanning of 170/252 legs

(67%) after a median of 69 months (39-75).

|

Overall outcome |

Number of legs |

% |

|

No remaining incompetence |

118 |

70 |

|

Some incompetence detected |

52 |

30 |

|

Primary groin surgery (All primary) |

104 (125) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

16 |

15 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

7** (+3 without incompetence#) |

7 |

|

Re-do groin surgery (All re-do) |

22 (45) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

6 |

27 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

4 |

18 |

|

Primary SSV* surgery |

30 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

2 |

7 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

8 |

27 |

|

Re-do SSV* surgery |

10 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

0 |

0 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

5 |

50 |

#2 stumps following laser ablation and 1 resulting

from open surgery **1 after laser.

V VCSS

The baseline VCSS score correlated with the CEAP clinical class (Figure 2). The median pre-operative score was 6 (range 1-22). The median baseline VCSS was significantly worse for patients who had re-do surgery (8 vs.6) p<.0001. Pain and swelling were commonly reported, 80 percent reported pain (32% daily) and 87% experienced leg swelling (51% already in the morning or afternoon). Compression stockings were used by 39%, always or most of the time. The VCSS improved significantly following surgery both at one year, 1 (range 0-10), and after the long-term follow-up, 2 (range 0-13) p<0.0001.

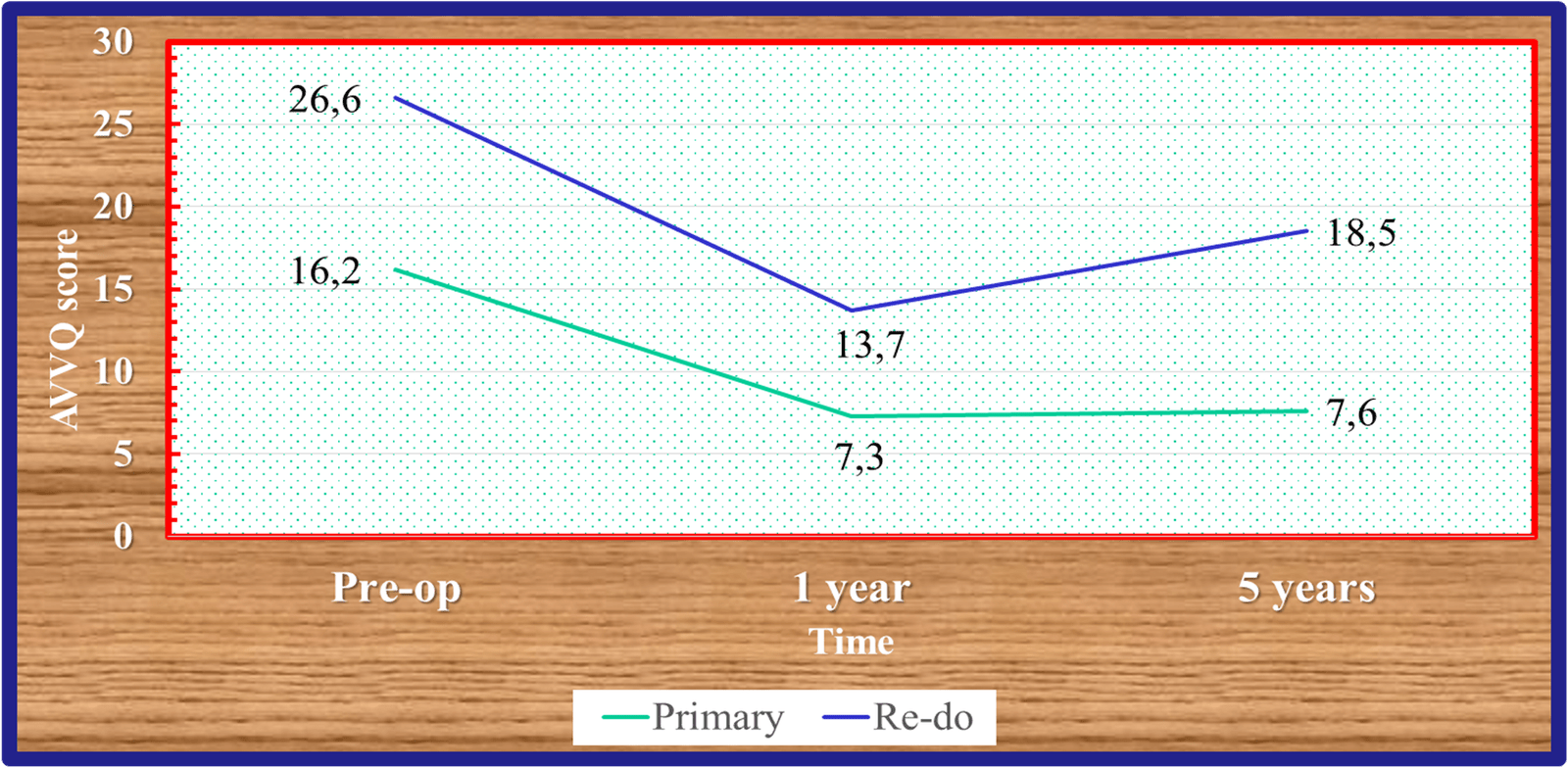

VI AVVQ

The baseline median AVVQ score was 20 (range 3-55) and was significantly reduced at one year 9 (range 0-53) and at the long-term follow-up, 10 (range 0-51) p< 0.001. Patients who had re-do surgery reported a significantly higher median baseline AVVQ score, 27 vs. 16 (p< 0.0001). The re-do scores deteriorated slightly between 1 year and the long-term follow-up contrary to primary procedures but remained significantly better than from the start (Figure 3).

Figure 2: The correlation between CEAP Clinical class and the Venous Clinical Severity Score.

Figure 3: Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire scores for primary and re-do patients during the audit.

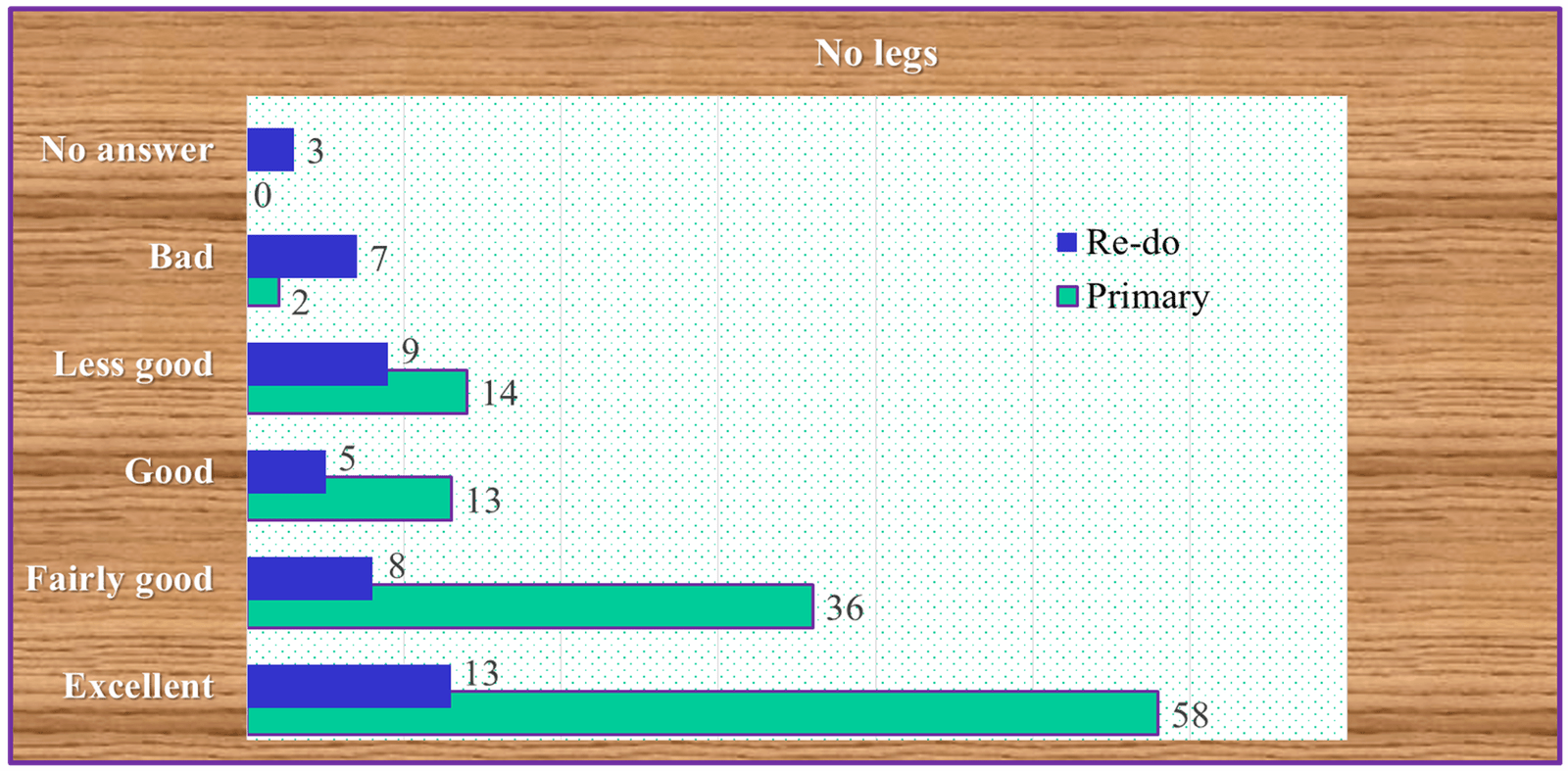

VII Patients’ Opinions Long Term

Eighty-eight per cent considered themselves symptomatically improved long term, with complete symptom relief for 44%, 26% reported some light remaining symptoms and for 18% some symptoms disappeared whilst others remained. Only 2% reported worsening of symptoms whilst 8% experienced no change and 2% did not respond. The great majority, 79% (130/165) reported a good to excellent cosmetic result (Figure 4), with a marked difference between primary and re-do patients. Only 9/168 were not satisfied with the overall result and an additional 15 patients were undecided.

Figure 4: Patients’ opinions regarding the long-term cosmetic result (>5 years) for primary and re-do surgery.

VIII Re-Do Groin Surgery

Open re-do groin surgery was undertaken in 33 patients due to remaining incompetent saphenous stumps, defined as a remnant of the proximal GSV/SFJ: 0.5 cm or longer. The anterior accessory saphenous vein was also incompetent in 13 legs (39%) and the rest had neovascularization from the stumps. All were operated on with a medial approach. After 12 months 30/33 were re-examined with CDU, no groin recurrence was shown for 73%, 13% had neovascularization and two showed stumps and neovascularization. Long term 22/33 could be re-examined with CDU and 13/22 groins (59%) showed no recurrence, two had neovascularization grade 1, four neovascularization grade 2 and three showed stumps with neovascularization grade 2.

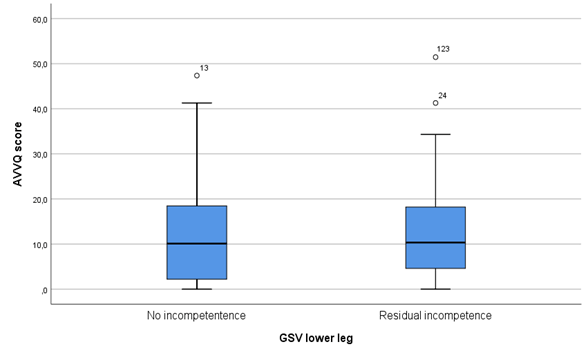

IX Residual Incompetent Lower Leg GSV

Out of 120 patients that had GSV surgery 70 had no detectable incompetence of the GSV below the knee while 50 had a CDU verified incompetence at the long-term follow-up. The AVVQ (p =0.604) and VCSS (p=0.208) scores were not significantly different between these two groups. The AVVQ median scores were 10,1 for competent or non- detectable lower leg GSVs and 10,3 for incompetent GSVs (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire scores for patients without remaining incompetence in the lower leg great saphenous vein and for those with remaining incompetence.

Discussion

This audit has shown that modern open venous surgery may lead to better surgical results than some RCTs comparing open surgery to endovenous ablation techniques seem to have indicated. Similar findings were recently reported from Japan based on a 5-year follow-up of patients having undergone modern minimally invasive GSV stripping [7]. Specifically, the clinical risk for early groin recurrence and especially neovascularization seems to have been overestimated or could have been the result of inadequate open surgical technique used in some RCTs [8, 9]. These findings have also been confirmed by long term follow-up from several RCTs, included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, that show more groin recurrence long term from endovenous techniques than from open surgery [10-12].

We have also been able to show long lasting improvement of disease severity (VCSS) and quality of life (AVVQ), even after re-do procedures. That re-do surgery leads to inferior results has been clearly shown underlining that it is extremely important to avoid recurrent varicose veins by performing a thorough primary intervention [13]. The most important measure is not to leave SFJ stumps behind, which is probably the reason for the higher numbers of groin recurrences long term from endovenous ablations in RCTs [10-12]. By employing a safety margin of 1-2 cm to avoid EHIT the result is in most cases a stump left behind, often connecting to tributaries and most often the anterior accessory saphenous vein. That the causes of recurrent varicose veins differed between endovenous procedures and open venous surgery was reported already in a review of midterm RCT results [14, 15].

Long term patient satisfaction was high and even though objective observers could detect remaining visible varicosities (in around 60% according to VCSS) and some remaining duplex detected reflux, the patients reported surprisingly good cosmetic results. Such recurrences could be labelled a “clinical recurrence” depending on the subjective judgement of the observer and it is a frequently used outcome variable in RCTs [15, 16]. Such a variable is perhaps of value in purely cosmetic interventions but is very difficult to interpret in studies where only symptomatic recurrences are being retreated. The problem is that a lot of the assessments for recurrence in RCTs showing similar figures for endovenous thermal techniques and open surgery (high ligation and stripping) were based on the variable “clinical recurrence”. The appropriateness of using “clinical recurrence” as an outcome variable, without stating symptomatic recurrence, could be questioned because it is difficult to interpret and to use as a variable aimed at measuring clinical success.

In the audit around 13% of all interventions were performed for symptomatic groin recurrence due to remaining incompetent stumps detected by CDU. All were operated on by a medial approach, developed and originating from our unit. One-year results have been published earlier and the present long-term results underline the durability of these results [17]. Most interesting is that the medial approach could be fulfilled in all cases and without any lymphatic leakage that was the main problem reported following other open re-do groin techniques [18-20]. The repeat procedures were mostly performed by one of four vascular surgeons and not just by one single “super-specialist”.

The necessity to treat an incompetent GSV below knee has become a matter of debate since endovenous methods, especially non-thermal can be performed with a minimal risk of nerve damage. Also, thermal techniques have been used more frequently and claimed to be safe and effective in preventing recurrence. In this audit the standard open surgical treatment for primary GSV incompetence was to perform invagination stripping down to knee level or slightly below. As a result, several incompetent lower leg GSVs were therefore left behind. At the long-term follow-up 50/120 were still incompetent but we found no statistically significant difference between the group with incompetent lower leg GSVs or those (70) with non-visible or competent veins, according to both VCSS and AVVQ-scores. This is in line with a previous case series where incompetent remaining lower leg GSVs did not seem to affect patient satisfaction [3]. Based on these data the need to treat the lower leg GSV can be questioned.

Although correctly performed modern open surgery, based on pre-operative CDU assessments, truly high ligation, invagination stripping and stab incisions for varicose clusters obviously leads to good long-lasting results, the open surgery has been downgraded in most clinical guidelines [21-23]. This despite most RCTs showing at least equal results regarding long term disease improvement and QoL. The long-term results seem to indicate that open surgery in fact leads to a lesser risk of developing groin recurrence that oven time might become symptomatic [9-11]. Based on results from open surgery it takes on average 8-9 years to develop symptoms from saphenous stumps [24]. Unfortunately, data based on long-term results appeared after publication of all present available guidelines and this new knowledge has therefore not been considered in current guidelines.

An audit like this one has the strength of being able to provide prospective real-world data and because of the thorough follow-up the long-term results are described in detail and looked at from various angles. There were more than 10 surgeons involved although four vascular surgeons performed more than 80% of the operations. The audit could be considered as a benchmark for what can be achieved by using mainly open surgical techniques in routine practice both regarding primary and repeat surgery. To be able to achieve this it is necessary to perform a thorough pre-operative CDU assessment and a radical surgical procedure. It is mandatory not to leave saphenous stumps and to minimise the surgical trauma by using invagination stripping and minimising the number and length of stab-incisions. The result evaluation was performed by vascular technologists that were blinded to the surgery performed both regarding VCSS and CDU assessments and therefore the results ought to be reliable. A flush laser ablation can be performed that most likely would avoid stump formation after endovenous treatments [25]. However, this technique was not used in any of the RCTs with a long-term follow-up and must be proven safe in additional studies, preferably RCTs.

There are obviously also weaknesses such as a single center audit and that we lost one third for the long-term follow-up. Half of them though for acceptable reasons such as very high age, incapacitating other disease, death or living in other parts of Sweden. The rest unfortunately, did withdraw from the voluntary long-term follow-up.

Informed Consent

All patients approved of participation in the audit by informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

This research received funding from Skaraborg Hospital research fund.

Article Info

Article Type

Research ArticlePublication history

Received: Mon 28, Jun 2021Accepted: Mon 12, Jul 2021

Published: Tue 27, Jul 2021

Copyright

© 2023 Olle Nelzen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.SCR.2021.07.15

Author Info

Corresponding Author

Olle NelzenDepartment of Research and Development and Vascular Surgery, Skaraborg Hospital Skövde, Skövde, Sweden

Figures & Tables

Table 1: Outcome from vein CDU scanning of 232/252 legs (92%)

after 12 months.

|

Overall outcome |

Number of legs |

% |

|

No remaining incompetence |

199 |

86 |

|

Some incompetence detected |

33 |

14 |

|

Primary groin surgery (All primary) |

137 (167) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

11 |

8 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

6** (+5 without incompetence#) |

8 |

|

Re-do groin surgery (All re-do) |

30 (65) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

4 |

13 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

3 |

10 |

|

Primary SSV* surgery |

34 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

4 |

12 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

2 |

6 |

|

Re-do SSV* surgery |

14 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

2 |

14 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

2 |

14 |

#3 stumps after laser ablation and 2

following open surgery **1 after laser.

Table

2:

Reasons for not attending the full long-term follow-up.

|

Reasons |

Number of patients |

|

Living in other counties |

27 |

|

High age or bad health |

6* |

|

Deceased |

9 |

|

Declined follow-up. |

12# |

|

Unknown reason |

30 |

|

Repeat surgery due to new/residual incompetence |

5** |

*1

declined CDU but responded to questionnaires.

#6

declined the CDU but responded to questionnaires.

**3

followed until re-do surgery and one full time after clearing a residual

incompetent perforator.

Table

3:

Outcome from vein CDU scanning of 170/252 legs

(67%) after a median of 69 months (39-75).

|

Overall outcome |

Number of legs |

% |

|

No remaining incompetence |

118 |

70 |

|

Some incompetence detected |

52 |

30 |

|

Primary groin surgery (All primary) |

104 (125) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

16 |

15 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

7** (+3 without incompetence#) |

7 |

|

Re-do groin surgery (All re-do) |

22 (45) |

|

|

Neovascularization |

6 |

27 |

|

Saphenous stumps |

4 |

18 |

|

Primary SSV* surgery |

30 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

2 |

7 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

8 |

27 |

|

Re-do SSV* surgery |

10 |

|

|

Stump + neovascularization |

0 |

0 |

|

Popliteal perforator incompetence |

5 |

50 |

#2 stumps following laser ablation and 1 resulting

from open surgery **1 after laser.

References

1. Carradice D, Mekako AI, Mazari FAK, Samuel N, Hatfield J et al. (2011) Clinical and

technical outcomes from a randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser

ablation compared with conventional surgery for great saphenous varicose veins.

Br J Surg 98: 1117-1123. [Crossref]

2. van den Bos R,

Arends L, Kockaert M, Neumann M, Nijsten T (2009) Endovenous therapies of lower

extremity varicosities: a meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg 49: 230-239. [Crossref]

3. Nelzén O, Fransson

I (2013) Varicose vein recurrence and patient satisfaction 10-14 years

following combined superficial and perforator vein surgery: a prospective case

study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 46: 372-377. [Crossref]

4. Eagan B, Donnely M,

Bresnihan M, Tierney S, Feeley M (2006) Neovascularization: an "innocent

bystander" in recurrent varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 44: 1279-1284.

[Crossref]

5.

De

Maeseneer M, Pichot O, Cavezzi A, Earnshaw J, van Rij A et al. (2011) Duplex

ultrasound investigation of the veins of the lower limbs after treatment for

varicose veins - UIP consensus document. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 42:

89-102. [Crossref]

6. De Maesener MG, Vandenbroeck CP, Hendriks JM, Lauwers PR, Van Schil PE

(2005) Accuracy

of duplex evaluation one year after varicose vein surgery to predict recurrence

at the sapheno-femoral junction after five years. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg

29: 308-312. [Crossref]

7. Kusagawa

H, Ozu Y, Inoue K, Komada T, Katayama Y (2021) Clinical Results 5 Years after

Great Saphenous Vein Stripping. Ann Vasc Dis 14: 112-117. [Crossref]

8. Versteeg MPT, Macfarlane J, Hill GB, van Rij AM (2016) The natural history

of ultrasound-detected recurrence in the groin following saphenofemoral

treatment for varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 4:

293.e2 -300.e2. [Crossref]

9. Strobel O, Bὔchler

MW (2013) The problems of the poor control arm in surgical randomized

controlled trials. Br J Surg 100: 172-173. [Crossref]

10.

Nelzén O (2016)

Reconsidering the endovenous revolution. Br J Surg 103: 939-940. [Crossref]

11. Hamann SAS, Giang

J, De Maeseneer MGR, Nijsten TEC, van den Bos RR (2017) Editor's Choice - Five

Year Results of Great Saphenous Vein Treatment: A Meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc

Endovasc Surg 54: 760-770. [Crossref]

12. Gassior SA, O’Donnel JPM, Aherne TM, Jalali A, Tang T et

al. (2021) Outcomes of Saphenous Vein Intervention in the

Management of Superficial Venous Incompetence: A Systematic Review and Network

Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg. [Crossref]

13. Beresford T, Smith

JJ, Brown L, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH (2003) A comparison

of health-related quality of life of patients with primary and recurrent

varicose veins. Phlebology 18: 35-37.

14. Bush RG, Bush P,

Flanagan J, Fritz R, Gueldner T et al. (2014) Factors associated with

recurrence of varicose veins after thermal ablation: results of the recurrent

veins after thermal ablation study. ScientificWorldJournal

2014: 505843. [Crossref]

15. O’Donnell TF, Balk

EM, Dermody M, Tangney E, Iafrati MD (2016) Recurrence of varicose veins after

endovenous ablation of the great saphenous vein in randomized trials. J Vasc

Surg: Venous and Lym Dis 4: 97-105. [Crossref]

16. Kheirelseid EAH,

Crowe G, Sehgal R, Liakopoulos D, Bela H et al. (2018) Systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials evaluating long-term outcomes of

endovenous management of lower extremity varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous

Lymphat Disord 6: 256-270. [Crossref]

17. Nelzén O (2013) A

medial approach for open redo groin surgery for varicose vein recurrence. Phlebologie

-Stuttgart 42: 247-252.

18. Hayden A,

Holdsworth J (2001) Complications following re-exploration of the groin for recurrent

varicose veins. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 83: 272-273. [Crossref]

19. De Maeseneer M

(2011) Surgery for recurrent varicose veins: toward a less-invasive approach? Perspect

Vasc Endovasc Ther 23: 244-249. [Crossref]

20. Nelzén O (2014)

Great uncertainty regarding treatment of varicose vein recurrence. Phlebologie

-Stuttgart 43: 13-18.

21.

Gloviczki P, Comerota

AJ, Dalsing MC, Eklof BG, Gillespie DL et al. (2011) The care of patients with varicose veins and

associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society

for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 53:

2S-48S.

[Crossref]

22.

National Institute

of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2013) Varicose veins: diagnosis and

management Clinical guideline [CG168]. NICE.

23.

Wittens C, Davies

AH, Bækgaard N, Broholm R, Cavezzi A et al. (2015) Editor's Choice - Management

of Chrongic Venous Disease: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European

Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 49:

678-737.

[Crossref]

24. Geier B, Stücker M, Hummel T, Burger P, Frings N et al. (2008) Residual stumps associated with inguinal varicose vein recurrences: a multicenter study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 36: 207-210. [Crossref]

25. Spinedi L, Stricker H, Hong Keo H, Staub D, Uthoff H (2020) Feasibility and safety of flush endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein up to the saphenofemoral junction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 8: 1006-1013. [Crossref]