Journals

The association between periodontal disease and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

A B S T R A C T

Background and Objective

Periodontal disease is a chronic infection and inflammatory condition of the tooth-supporting tissues. Dementia is a degenerative condition of the brain affecting memory and brain function. The objective of this review is to evaluate associations between the two conditions.

Methods

Systematic review with meta-analysis of published articles that involved participants aged ≥45 years with either periodontal disease or dementia. Electronic database searches of PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus were conducted to source articles that met the inclusion criteria. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used for quality appraisal. Two random effects meta-analyses were conducted to investigate the bi-directional association between periodontitis and dementia.

Results

Of 1,670 titles and abstracts found, quality assessment was conducted on 23 articles that met the inclusion criteria. Eight articles presenting findings on the association between dementia and periodontitis, and four studies on the converse association, were subsequently combined into meta-analysis. People with periodontal disease are more likely to suffer from dementia (Odds Ratio=1.17, 95% CI=1.02-1.34, P heterogeneity=0.33, I2 =13%). Conversely, people with dementia are 69% more likely to have periodontal disease (Odds Ratio =1.69, 95% CI=1.23-2.30, P heterogeneity=0.00, I2 =76%).

Conclusion

A bi-directional association exists between periodontitis and dementia. With the aging population increasing, degenerative conditions such as dementia and periodontal disease are becoming more common. Family members and healthcare providers need to be aware that the effects of dementia may impede adequate oral hygiene, the cornerstone of prevention of periodontitis, and increase the likelihood of periodontal disease.

Keywords

Periodontitis, gingival diseases, cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Periodontal diseases affect one or more of the periodontal tissues that have traditionally been divided into two categories: non-destructive inflammation of the gingival tissues in a condition known as ‘gingivitis’ and destructive inflammation termed ‘periodontitis’ which is characterized by progressive breakdown of alveolar bone and, in some instances, dental mobility [1]. Periodontal disease, more narrowly defined as chronic periodontitis, is characterized by gingival recession and/or pocket formation surrounding teeth in response to accumulation of predominantly gram-negative bacteria around the tissues. Almost half the U.S. population express signs of periodontal disease, the prevalence increasing with age to include 70% of people over 65 years [2]. Australian findings are comparable to the U.S. population; 44% of those aged 55-74 years and 61% of Australians aged 75 years or older exhibit evidence of ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ periodontitis [3]. Dementia is defined as a reduction in the capacity of cognitive function with aging relative to previous mental ability and includes a set of symptoms such as memory loss, difficulty in speaking and writing, and changes in mood. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, is characterised by neuronal loss, the presence of senile plaques containing β-amyloid (Aβ) protein, and neurofibril¬lary tangles of hyper-phosphorylated tau protein [4-6]. Similar to periodontal disease, the prevalence of dementia increases from approximately five percent of adults aged 65 years to one third of people aged over 85 years [6].

Periodontal disease is a common source of chronic infection given transient bacteremia occurs following oral hygiene procedures and mastication [7-10]. In vivo, these have been found to contribute to atherosclerosis in animals, with seropositivity to the periodontal pathogens Porphoramonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans being positively associated with the prevalence of coronary heart disease among Finnish men [11-13]. A recent retrospective investigation involving data from 27,963 Taiwanese people aged over 50 years reported that having chronic periodontitis increases ones’ risk of developing AD by 70% over 10 years, however, this association was partially mediated by co-occurrence of cerebrovascular disease [14]. Viable periodontal pathogens have been shown to invade atheromatous tissue in culture [15]. Further, evidence that periodontal microbes permeate the blood-brain barrier exists as bacterial lipopolysaccharides have been detected from post-mortem sections of AD sufferers [16].

A number of studies have recently been published that have examined the association between periodontal disease and dementia. The purpose of this investigation is to summarize the evidence of association via systematic review and meta-analysis, in an effort to provide the most contemporary scientific evidence.

Materials and Methods

PICO

Population: Middle to elderly adults defined as being 45 years or older.

Intervention (exposure): Clinically defined periodontitis based on probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment loss (CAL), gingival bleeding (or a combination thereof).

Comparator: Middle to elderly adults aged 45 years or older without clinically defined periodontitis.

Outcome: Dementia including Alzheimer’s disease where the primary aetiology is not due to cerebrovascular events or genetic/congenital conditions.

Study registration

The protocol for this systematic review has been registered with PROSPERO: CRD42018115547

Study designs included in this review

The present review targeted associations between periodontal disease and dementia. Therefore, only cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies were included.

Type of participants

This review focuses on the association between periodontal disease and the most common forms of dementia arising from degenerative conditioning of the brain. As such, study participants had to be aged 45 years or older and not had dementia attributed to cerebrovascular events or genetic/congenital conditions.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they measured periodontal status via clinical oral assessments of PPD, CAL, gingival index (GI), bleeding on probing (BOP), modified community periodontal index (MCIP), alveolar bone loss (ABL), and/or plaque index (PI). Studies solely defining periodontitis based on radiographic evidence, visual-only criteria or tooth-loss were excluded. For dementia, studies were included if a verified cognitive test was used to ascertain dementia. Such tests included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Mini-Mental State Examination Korean version (MMSE-KC), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), Spatial Copying Task (SCT), Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), defined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM- IV), Word Fluency (WF), and the criteria developed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA).

Search strategy and sources

Electronic searches for PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus databases were developed with the aid of a university research librarian based on the criteria presented in (Supplement Table 3). For each of the four databases, searches commenced from their earliest respective records to October 20, 2018. Only studies published in English were included. Three reviewers (Kapellas, Ju and Wang) screened titles and abstracts, all of whom are dental clinicians and experienced in epidemiology. Full-texts of studies meeting the review eligibility criteria were sourced and the relevant data was extracted as per (Supplement Tables 1 and 2). In the event of disagreement, discussion with the intention to reach consensus between the three reviewers was performed.

Quality assessments

Each study was evaluated according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case-control and cohort studies [17]. A modified version of the NOS was used for cross-sectional studies (Supplement Tables 4-6) [18]. Qualitative assessment of each scale comprised three main items: sample selection, comparability and outcome (exposure). The maximum score for cross-sectional studies was 10. Articles that were assigned with 9-to-10 stars were deemed to be of ‘High’ quality, while scores 7-to-8 were ascribed as being of ‘Moderate’ quality and scores 6 or lower were deemed to be of ‘Low’ quality. The maximum score for both cohort and case-control studies was nine. Articles that were assigned with values of 8-to-9 were classified as ‘High’ quality, while a score of 7 was assigned ‘Moderate’ quality and ‘Low’ were assigned for studies with 6 or less stars.

Data Extraction

Data from each study included: 1) author and year of publication, 2) country of study, 3) sample size and population of focus, 4) study design, 5) dementia definition, 6) periodontitis case definition, and 7) main study findings.

Statistical analysis

Random effects meta-analysis was used to generate pooled summary estimates and forest plots. Odd ratios (ORs) and respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to evaluate the association between periodontal disease and dementia. Study weights were utilized accounting for differences in study design to facilitate population-level inferences. The I2 statistic was used to quantify the heterogeneity between studies, an I2 > 75% and p>0.05 was considered indicative of significant (high) heterogeneity [19, 20]. Analysis was undertaken using the MetaXL 5.3 (Epigear International [www.epigear.com]) add-on program for Microsoft Excel. This review was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [21].

Results

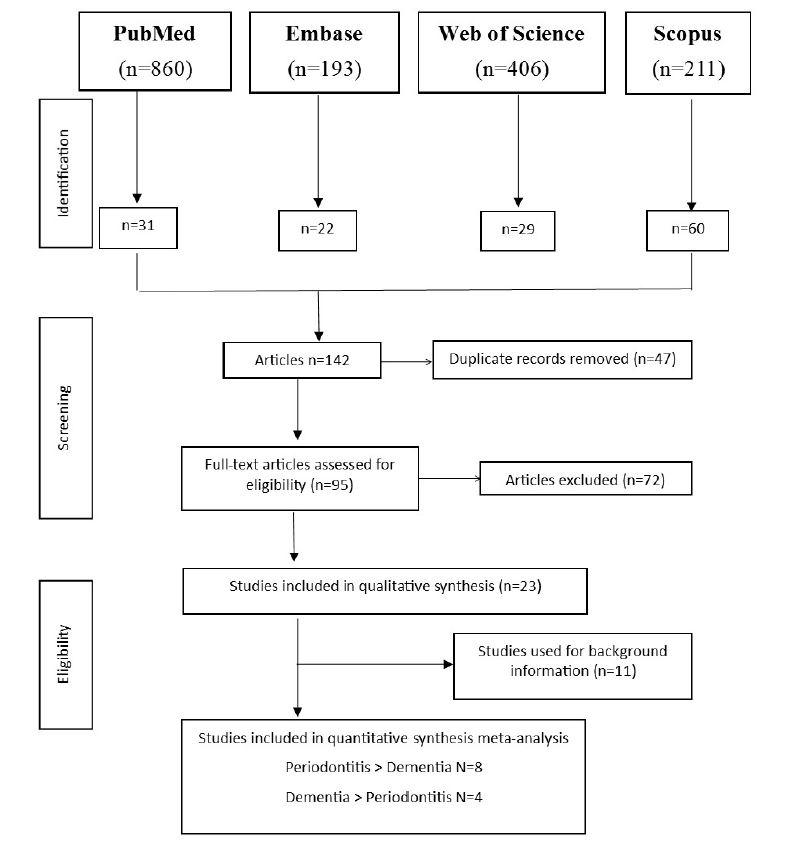

Figure 1 shows the flowchart for the four databases. Some 1,670 titles and abstracts were found through the four electronic searches. Following screening, removal of duplicates and exclusions, quality assessment was conducted on 23 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Eight articles that presented findings on the association between dementia and periodontitis, and four studies on the converse association, were subsequently combined for meta-analyses.

Description of included studies

Descriptive summaries of 23 included articles published between 1994 and 2018, are chronologically presented in (Supplement Tables 1 and 2) [14, 22-44]. The studies were conducted in four continents including Europe, North America, South America and Asia (Supplement Tables 1 & 2) [14, 22, 23, 26-35, 38-45]. The number of participants in each study ranged from 42 in the study by Ship and Puckett to 27,963 in the study by Chen [14, 38]. Six of 20 included studies were cross sectional, six were case–control studies while the remaining 11 were cohort studies [14, 22-32, 34, 35, 37-44]. Tests for dementia were based on the NINCDS-ADRDA for six studies, nine studies used the MMSE test or its Korean variant, three used the DSST test, the DSM-III-R or IV test or used the ICD-9-CM criteria, one study used the combined DWR and WF test, while individual studies used either the SCT test, or WAIS and BDT test [14, 22-34, 37, 38, 40-44].

Association between periodontal disease and dementia

A number of studies reported that people with periodontal disease were more likely to also show evidence of cognitive impairment as expressed by lower test scores in either the DSST, BDT, MMSE, DWR and/or WF [26-29, 33, 34, 37, 43, 44]. In contrast, the study by Syrjälä reported no associations between periodontal disease and cognitive decline [41]. Four studies were combined into meta-analysis to quantify the association between periodontal disease and dementia [14, 26, 31, 42]. People with periodontal disease were more likely to suffer from dementia (OR=1.17, 95% CI=1.02-1.34, P heterogeneity=0.33, I2 =13%) (Figure 2) compared to people without periodontal disease.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the search process.

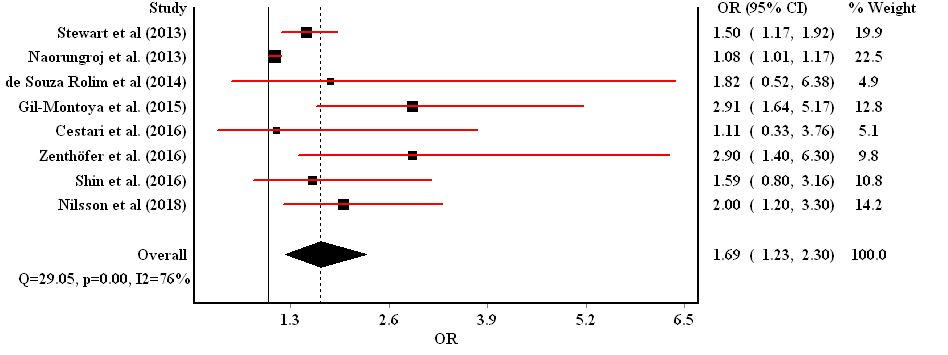

Association between dementia and periodontal disease

The majority of studies investigating the association between dementia and periodontal disease reported that people with dementia more commonly had teeth with deep periodontal pockets, higher levels of loss of attachment and greater proportions of periodontal sites with bleeding compared to people without dementia [23, 28, 29, 33-35, 37, 39, 40, 44]. Eight studies were combined into meta-analysis to quantify the association between dementia and periodontal disease [22-24, 33, 34, 36, 37, 39, 44]. People with dementia were 69% more likely to have periodontal disease (OR=1.69, 95% CI=1.23-2.30, P heterogeneity=0.00, I2 =76%) (Figure 3) compared to people without dementia.

Figure 2: Forest plot for the association between dementia and periodontal disease.

Figure 3: Forest plot for the association between periodontal disease and dementia.

Discussion

This systematic review reports a positive bidirectional association between periodontal disease and dementia. Given the prevalence of periodontitis and various dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease increase with age, positive associations are expected. The present findings concur with other reviews recently published in this field [46-49]. Poor oral hygiene, periodontal disease and dental morbid¬ity have been correlated with the presence and increased severity of dementia [40]. Plausibly, dementia may reduce one’s ability to partake in effective oral hygiene, leading to the development or progression of periodontal disease. In a study associating P. gingivalis IgG seropositivity with cognitive impairment using NHANES III data, Noble and colleagues speculated that a person with established dementia is more likely to be inattentive to oral health maintenance and oral hygiene and thus possess a higher microbial burden [50]. Furthermore, Yu and colleagues highlighted that cognitive impairment was a significant risk factor for the incidence of periodontal disease in non-institutionalized older adults [43]. Severe periodontitis is also likely to result in tooth loss, which may influence mastication leading to dietary change, potentially affecting nutritional intake. A lack of key vitamins and nutrients such as vitamin B has been related to cognitive impairment [29].

Chronic periodontal inflammation and infection contribute to brain amyloid accumulation in older age, which is associated with impaired cognition [51]. Sys¬temic inflammation has been shown to pre¬dict dementia prospectively [52-54]. Though the causal relationship between periodontal disease and cognitive impairment is not fully understood, systemic inflammation may provide some interpretation. People with chronic diseases such as periodontitis, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, possess higher levels of systemic markers of inflammation in their blood serum, saliva or gingival crevicular fluid [55]. People with these chronic conditions may potentially have a heightened systemic inflammatory response represented as the release of a large amount of cytokines and soluble mediators such as interleukins and prostaglandins which are involved in the activation of tissue and bone destruction evident in periodontal disease [53, 56].

In this systematic review, we report the results of a comprehensive undertaking to analyze the literature published through to October 2018 reporting on the association between periodontal disease and dementia. As expected, our meta-analyses provided convincing and reliable evidence relevant to periodontal disease and dementia. One strength of this review is that adjusted estimates were used in both meta-analyses. Secondly, the meta-analysis on the association between periodontitis and dementia was composed of four cohort studies. In the absence of randomised trials, cohort studies provide the best available evidence. In contrast, the meta-analysis of the association between dementia and periodontitis consisted of a combination of one cross-sectional, four case-control and three cohort studies, which may be interpreted as a potential limitation. While the odds estimates were consistent across these eight trials, an I2 of 76% is indicative of high heterogeneity across studies suggesting the OR of 1.69 (95% CI 1.23-2.30) may be biased [19].

A constant challenge when conducting any systematic reviews of periodontal disease are the different case definitions used as they can influence overall estimates. The cohort study by Iwasaki and colleagues (26) included in this review is a prime example. They assessed the association between periodontitis and cognitive impairment across both the European Workshop in Periodontology (where ‘severe’ periodontitis was associated with an adjusted OR 3.58 (95% CI 1.45-8.87)) and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and American Academy of Periodontology definition of ‘severe’ periodontitis where the adjusted OR was 2.61 (95% CI 1.08-6.28). In an effort towards pragmatism, the odds ratio derived from the CDC-AAP definition was used in the present review. Randomised trials to assess for a causal relationship are unlikely feasible given the potential challenges in providing comprehensive periodontal treatment in a group with dementia. Additionally, the costs of designing a trial to treat periodontitis and prospectively assess study participants for the incidence of dementia are also likely to be prohibitive. Additional longitudinal studies are unlikely to influence these associations further. Findings from this review should be used to increase the awareness of those charged with the care of people with dementia.

Table 1: Studies on the association between dementia and periodontal disease

|

Author/year |

Country |

Sample Size |

Study Design |

Dementia Definition |

PD Definition |

Main finding |

|

Ship 1994 |

USA |

Total N=42 mean age 65 years (range 48-90) Alzheimer’s Disease N=21 without Alzheimer’s Disease N=21 |

C/C |

NINCDS-ADRDA MMSE for severity

|

PI, GB, PPD, LOA |

Oral health parameters including tooth surfaces with dental plaque, sites with gingival bleeding and calculus were significantly worse in the AD group compared to control. Non-significant trend for poorer gingival health with lower MMSE scores. No significant difference in PPD, recession and LOA between AD and controls. |

|

Syrjälä 2007 |

Finland |

Total N=2,320 aged ≥55 years MMSE 16-12 N=1,892 MMSE 11-10 N=297 MMSE ≤ 9 N=131 |

C/S |

Shortened MMSE: Cognitive impairment = ≤11 |

≥1 site PPD ≥4mm |

People with mild-severe cognitive impairment had, on average, fewer teeth in total and more carious teeth than ‘healthy’ people. There were fewer teeth with PPD ≥4mm among individuals with cognitive impairment mean (SD) 3.7 (4.7) compared to ‘healthy’ people 4.6 (5.5). |

|

Yu 2008 |

Taiwan |

Total N=803 aged ≥60 years DSST Score <34 Q1 N=233 DSST Score 34-45 Q2 N=193 DSST Score 46-57 Q3 N=188 DSST Score >57 Q4 N=199 |

C/S |

DSST: No cut-off score provided. Higher scores indicate higher cognitive function |

PPD ≥3mm, ≥10% sites CAL ≥4mm, ≥10% sites not on same site or tooth |

Periodontal disease was more common in people with low DSST scores. Odds of periodontal disease with increasing (continuous) DSST score 0.69 (95% CI 0.51-0.94), P=0.02. Compared to Q1: Q2 OR 0.60 (95% CI 0.34-1.08), Q3 0.54 (95% CI 0.28-1.07), Q4 0.43 (95% CI 0.18-1.02); P trend=0.04. |

|

Kaye 2010 |

USA |

Total N=597 men aged 28-70 years MMSE: Low N=95, Normal N=500 SCT: Low N=185, Normal N=412 |

Co |

MMSE: Cognitive impairment = <25; SCT: Cognitive impairment = <10 |

CPI score ≥ 2 PPD & Recession >1mm |

Trend for higher mean PPD ≥4mm among men with ‘low’ MMSE & SCT scores compared to ‘normal’. Progression of PD stratified by median age 45.5years: 10-year adjusted HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.01-1.09) for PD progression for ‘low’ MMSE score; 10-year adjusted HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.01-1.06) for PD progression for ‘low’ SCT score. |

|

Rai 2012 |

India |

Total N=107 Dementia N=20 (age range 59-69 years) Healthy control N=32 (age range 58-69 years) Severe periodontitis N=55 (age range 60-69 years) |

C/C |

|

Dental plaque, GI, BOP, PPD & CAL. |

Adjusted for age: dental plaque, GI, BOP, PPD & CAL significantly higher for people with dementia and periodontitis compared to controls. Mean PPD (SD) dementia: 4.81 (0.78), ‘severe periodontitis’: 2.85 (0.67), ‘healthy’: 1.89 (0.67). |

|

Kamer 2012 |

Denmark |

Total N=152 (aged 70 years)

|

C/S |

WAIS, DST: Cognitive impairment score <29 BDT: Cognitive impairment score <32 |

MCPI score ≥3 indicative of PPD ≥4mm |

70% of sample had MCPI. Mean (SD) DST score significantly lower for people with MCPI score ≥3: 33.4 (10.5) compared to 41.0 (10.7) for those with MCPI ≤2. Mean (SD) BDT score significantly lower for people with MCPI score ≥3: 31.2 (7.9) compared to 33.0 (6.8) for those with MCPI ≤2. Crude OR for ‘low’ DST score among MCPI score ≥3 =5.38 (95% CI 1.97-14.73). Crude OR for ‘low ’BDT score among MCPI score ≥3 =3.26 (95% CI 1.26-8.38) if lost <10 teeth, and BDT OR 0.41 (95% CI 0.84-2.04) if lost ≥11 teeth. |

|

Syrjälä 2012 |

Finland |

Total N=354 aged ≥75 years, mean (SD) 82.0 (4.9) years Without dementia N=278 AD N=49 Vascular dementia N=16 Other dementia type N=11 |

C/S |

DSM-IV: Dementia severity defined by DSM-III-R ‘mild’=33, ‘moderate’=24, ‘severe’=19 |

PPD ≥4mm |

49.2% of sample edentulous. Mean (SD) teeth of people with AD: 10.9 (7.0) compared to 15.0 (8.2) for those without dementia. Adjusted RR of PPD ≥4mm with AD: 1.4 (95% CI 0.9-2.1), other dementia types adjusted RR 2.5 (95% CI 1.5-4.1). Crude RR of PPD ≥4mm with ‘mild’ dementia: RR 1.4 (1.0–2.0), ‘moderate or severe’ dementia: RR 1.5 (1.0–2.1). |

|

Stewart 2013 |

USA |

Total N=1,053 aged 70-79 years, mean (SD) 73.5 (2.8) years

|

Co |

3MS: Cognitive impairment = score <80, DSST: 20% decline in 5-years |

PPD ≥3mm; LOA ≥3mm GI (0-3), plaque score & BOP |

Cognitive decline over 5 years reported in ascending order by oral health parameter quartile. Extent of PPD ≥3mm: Q1 4.5%, Q2 4.1%, Q3 2.6%, Q4 11.7%. Odds for cognitive decline per quartile increase in extent of PPD ≥3mm: OR 1.50 (95% CI 1.17–1.92); Gingival index score: Q1 2.0, Q2 3.9, Q3 6.1, Q4 15.5%. Odds for cognitive decline per quartile increase in GI: OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.66–2.67); |

|

Naorungroj 2013 |

USA |

Total N=5,878 aged 46-65 years, mean (SD) 56.8 (5.7) years

|

Co |

DWR, WF, DSST |

CDC/AAP ‘severe’ definition & gingival inflammation |

Cognitive decline over 6 years reported. All estimates adjusted for age, sex and race. Adjusted OR for ‘severe’ periodontitis: DWR: OR 1.01 (95% CI 0.94, 1.09); DSST: OR 1.08 (95% CI 1.01, 1.17) WF: OR 1.00 (95% CI 0.93, 1.07). Adjusted OR for ‘extent gingival inflammation’: DWR: OR 0.29 (95% CI -0.47, 1.06); DSST: OR 1.22 (95% CI 0.45, 1.99), WF: OR 0.66 (95% CI -0.09, 1.41). |

|

de Souza Rolim 2014

|

Brazil |

Total N=59 aged 59-91 years, Control group N=30 mean (SD) 61.2 (11.2) years Dementia group N=29 mean (SD) 75.2 (6.7) years |

C/C |

NINCDS-ADRDA criteria equivalent to MMSE scores 18-26 |

PI ≥30% GBI ≥20% PPD >3mm & CAL >3mm |

Periodontal infections were significantly more frequent in patients with dementia than in healthy subjects. 31% of dementia group had gingivitis compared to 10% of control group. 27.6% of dementia group had ‘moderate’/’severe’ periodontitis compared to 16.7% of control group. |

|

Martande 2014 |

India |

118 subjects: aged 50-80 years Dementia group N=58 mean (SD) 65.2 (7.3) years. Control group N=60 mean (SD) 64.5 (9.4) years |

C/S |

NINCDS-ADRDA MMSE scores: ‘mild’:21-25 N=22, ‘moderate’: 11-20 N=18, ‘severe’ ≤10 N=18 |

PI, GI, PPD, CAL, REC |

Oral health parameters stratified by MMSE scores. Mean (SD) GI scores: control 0.64 (0.21), ‘mild’ 1.15 (0.21), ‘moderate’ 1.68 (0.22), ‘severe’ 2.31 (0.26). Mean (SD) PPD scores: control 2.39 (0.55), ‘mild’ 3.18 (0.35), ‘moderate’ 3.99 (0.32), ‘severe’ 5.02 (0.56). |

|

Gil-Montoya 2015 |

Spain |

Total N=409 aged 51-98 years Control group N=229 mean (SD) 78.5 (7.9) years. Dementia group N=180 mean (SD) 77.0 (7.8) years.

|

C/C |

DSM-IV, NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. ‘mild’ cognitive impairment N=21, ‘mild/moderate’ dementia N=123, ‘severe’ dementia N=36 |

PI, BI, PPD, AL by % of sites with AL >3 mm as follows: 0%=Non-PD, ‘mild’ PD = 0-32%, ‘moderate’ PD = 33% - 66%, ‘severe’ PD = 67% to 100% |

People with cognitive impairment/dementia had significantly fewer teeth mean (SD) 15.3 (8.0) compared to controls 17.4 (8.0), P=0.008. Mean (SD) BI scores: control 50.6% (34.2), ‘cognitive impairment/dementia’ 63.0 (31.1), P=<0.001. Mean (SD) PPD scores: control 2.6 (1.5), ‘cognitive impairment/dementia’ 3.0 (0.7), P=<0.001. ‘Mod/severe’ AL more common among ‘cognitive impairment/dementia’ group 90% versus 75.5% for controls. Odds of ‘moderate’ AL 2.58 (95% CI 1.31 - 5.09), OR ‘severe’ AL 3.04; (95% CI 1.69 - 5.46). |

|

Cestari 2016 |

Brazil |

Total N=65 aged 56-92 years. AD N=25 mean (SD) 77.7 (6.0) years MCI N=19 mean (SD) 73.1 (6.8) years. Control group N=21 mean (SD) 75.3 (5.8) years |

C/C

|

NINCDS-ADRDA |

PI, BI, PPD, CAL |

Study compared people with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment to ‘healthy’ controls. No significant difference between the three groups in terms of periodontitis case: AD 40.0%, MCI 26.3%, ‘healthy’ 42.5%. Mean PPD was also non-significantly difference between the three groups mean (SD): AD 2.8 (1.7), MCI 3.1 (1.6), ‘healthy’ 2.6 (3.3). |

|

Shin 2016 |

Korea |

Total N=189 aged 60-86 years. Cognitively impaired N=65 mean (SD) 69.7 (6.4) years Cognitively normal N=124 mean (SD) 68.7 (4.9) years. |

C/C |

MMSE-KC |

‘moderate’ PD ≥2 interproximal sites with RABL ≥4 mm), ‘severe’ PD ≥2 interproximal sites with RABL≥6 mm |

More people with cognitive impairment had periodontitis 36.9% compared to those cognitively normal 23.4%, P=0.049. People with a history of periodontitis were more likely to have cognitive impairment: adjusted OR: 2.14 (95% CI 1.04-4.41). |

|

Zenthöfer 2017 |

Germany |

Total sample N=219 aged 54-102 years Dementia N=136 mean (SD) 84.6 (8.1) years Non-dementia N=83 mean (SD) 80.7 (9.8) years |

C/S

|

MMSE score <20 |

GBI, CPITN, DHI ‘Moderate’ periodontitis: codes 1-3 ‘Severe’ periodontitis: code 4 |

42% of sample edentulous. Mean (SD) CPITN score significantly higher among dementia group 3.1 (0.7) compared to non-dementia group 2.7 (0.6), P <0.01. Non-significant difference in GBI scores between dementia mean (SD) 53.8 (27.6) compared to non-dementia 48.8 (28.9). ‘Severe’ periodontitis was more common: OR 2.9 (1.4- 6.3) among people with dementia. Dementia does not influence GBI OR: 0.5 (-8.6-12.5). |

|

Nilsson 2018 |

Sweden |

Total N=704 aged 60-96 years. Cognitive decline N=115 No decline N=589 |

Co |

MMSE ≥3 points deterioration over six years |

≥4mm bone loss at ≥30% of tooth sites |

83% of those with cognitive decline aged ≥72 years. 59% of people experiencing cognitive decline had periodontal bone loss which was significantly higher than the 34% without cognitive decline P<0.01 Odds of cognitive decline among those with periodontal disease: Adjusted OR 2.0 (95% CI 1.2-3.3). |

C/S: cross-sectional, C/C: case-control, Co: cohort, RR: risk ratio, OR: Odds Ratio, HR: hazard ratio, SD: standard deviation, CI: confidence interval.

ABL: alveolar bone loss, AL: attachment loss, BI: bleeding index, BOP: bleeding on probing, CAL: clinical attachment level, CDC/AAP: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology CP: chronic periodontitis, CPITN: community periodontal index of treatment need, GBI: gingival bleeding index, GI: gingival index, LOA: loss of attachment, MCIP: modified community periodontal index, PD: periodontal disease, PI: plaque index, PPD: probing pocket depth, RABL: radiographic alveolar bone loss.

3MS: Modified mini mental state examination, WAIS: Wechsler adult intelligence scale, MMSE: mini-mental state examination, SCT: spatial copying task, DSST(DHI: denture hygiene index, DST): digit symbol substitution test, BDT: block design test, DSM-IV: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, DSM-III-R: diagnostic and mental Disorders, DWR: delayed words recall, WF: word fluency, Clinical Modification, (NINCDS-ADRDA): Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders association, MMSE-KC: mini-mental state examination Korean version, D: Dementia, ND Non-Dementia, AD: Alzheimer’s Disease, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, ADAS-cog: Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale.

Table 2: Studies on the association between periodontal disease and dementia

|

Author/year |

Country |

Sample Size |

Study Design |

Dementia Definition |

PD Definition |

Main finding |

|

Tzeng 2016 |

Taiwan |

Total N= 8,828 aged ≥20 years. Periodontitis cases N=2,207 Non-periodontitis cases N=6,621

|

Co |

DSM-IV |

ICD-9-CM codes: 523.4 (chronic periodontitis) and 523.1 (chronic gingivitis) |

25 (1.1%) of periodontitis cases developed dementia over a 10-year period compared to 61 (0.9%) on non-periodontitis cases, P=0.04. Adjusted HR: 2.54 (95% CI 1.55–4.16) equivalent to 510.6/100,000 population periodontitis cases compared to 248.9/100,000 population for non-periodontitis cases. |

|

Iwasaki 2016 |

Japan |

Total N=85 mean (SD) 79.3 (3.7) years. Non-severe PD N=64 Severe PD N=21 |

Co

|

MMSE must have score ≥24 at baseline. |

CDC/AAP ‘severe’ classification |

Three-year follow-up period. No significant difference between mean (SD) MMSE scores: Non-severe PD: 27.6 (1.9), severe PD: 27.6 (2.1). ‘Severe’ periodontitis was associated with increased risk of MMSE decline over 3 years relative to ‘non-severe’ periodontitis: Adjusted RR 2.2 (95% CI 1.1-4.5) |

|

Ide 2016 |

UK |

Total N=52 mean (SD) 77.7 (8.6) years. Periodontitis cases N=20 mean (SD) 74.9 (2.0) years. Non-periodontitis cases N=32 mean (SD) 79.4 (1.3) years. |

Co

|

NINCDS-ADRDA (ADAS-COG, MMSE) |

CDC/AAP |

No significant difference in baseline MMSE scores between periodontitis mean (SD) 19.5 (1.0) and non-periodontitis groups 21. (0.9). No significant difference in baseline between ADAS-COG scores between periodontitis mean (SD) 46.8 (2.2) and non-periodontitis groups 45.7 (2.2).

Study participants followed-up for 6-months: significant change in ADAS-COG score: between group adjusted mean (95% CI) 4.9 (1.2 – 8.6). Non-significant change in sMMSE score between group mean (95%) -1.8 (-3.6-0.04). |

|

Chen 2017 |

Taiwan |

Total N=27,963 aged ≥50 years. With chronic periodontitis N=9,291 mean (SD) 54.1 (10.5) years. Without chronic periodontitis N=18,672 mean (SD) 54.2 (10.5) years. |

Co |

AD (ICD-9-CM code 331.0) |

Chronic periodontitis (ICD-9-CM code 523.4) |

Study participants followed-up over mean 12 years. 1-year risk of Alzheimer’s disease risk among people with periodontitis: adjusted HR: 1.30 (1.00–1.70). 10–year risk of Alzheimer’s disease risk among people with periodontitis: HR: 1.71 (1.15–2.53). |

|

Lee 2017 |

Taiwan |

Total N-6,056 aged ≥65 years. With periodontitis N=3,028 mean 72.4 years. Without periodontitis N=3,028 mean 72.4 years. |

Co |

AD (ICD-9-CM codes 290.0-290.4, 294.1, 331.0-331.2) |

Chronic periodontitis (ICD-9-CM code 523.3-5) |

Follow-up period not explicitly stated but is ~8 years. Periodontitis and non-periodontitis comparable at baseline except for geographical location or residence. Adjusted HR for dementia among those with periodontitis: 1.16 (95% CI 1.01-1.32). |

|

Lee 2017 |

Taiwan |

Total N=182,747 with periodontitis aged ≥45 years. Dental prophylaxis N=97,802 Intensive periodontal treatment N=5,373 Tooth extraction(s) N=59,898 No treatment N=19,674 |

Co |

AD (ICD-9-CM codes 290.0-290.4, 294.1, 331.0) |

ICD-9-CM code 523.0-523.5 |

10-year follow-up period. 6,133 developed dementia, resulting in an IR for dementia of 0.47%/year. Adjusted HRs for dementia based on treatment received: intensive treatment: HR 1.18 (0.97-1.43), extraction: HR 1.10 (1.04-1.16), no treatment: HR 1.14 (1.04-1.24). |

|

Iwasaki 2018 |

Japan |

Total N=179 aged ≥75 years, mean (SD) 80.1 (4.4) years. CDC/AAP ‘severe’ N=49 mean (SD) age 79.9 (4.0) CDC/AAP ‘non-severe periodontitis’ N=130 mean (SD) age 80.2 (4.6) |

Co |

MMSE & DSM-IV |

EWP & CDC/AAP ‘severe’ classifications |

5-year follow up period. Adjusted OR for MCI based on EWP ‘severe’ periodontitis definition: 3.58 (95% CI 1.45-8.87) compared to ‘non-severe’ periodontitis. Adjusted OR for MCI based on CDC/AAP ‘severe’ periodontitis definition: 2.61 (95% CI 1.08-6.28) compared to ‘non-severe’ periodontitis. |

Co: cohort, RR: risk ratio, OR: Odds Ratio, HR: hazard ratio, IR: incidence ratio, SD: standard deviation, CI: confidence interval.

CDC/AAP: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology, CP: chronic periodontitis, EWP: European Workshop on Periodontitis, PD: periodontal disease.

ADAS-cog: Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale, DSM-IV: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, MMSE: mini-mental state examination, (NINCDS-ADRDA): Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders association.

Conclusion

An association exists between periodontitis and dementia. Family members and healthcare providers need to be aware that the effects of dementia may impede adequate oral hygiene and increase the likelihood of periodontal disease.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the assistance of The University of Adelaide research librarian Michael Draper (retired) for his guidance in generating the four database search criteria. This work was supported by an Early Career Fellowship [grant number 1113098 to KK] and Senior Research Fellowship [grant number 1102587 to LMJ] both from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council; and the Longgang Ear Nose and Throat Hospital travel fellowship granted to XW.

Acknowledgement

S1 PRISMA Checklist

Supplement Table 1: Search Strategy

Supplement Tables 2 — 4 Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Assessments

Conflict of Interests

None

Article Info

Article Type

Research ArticlePublication history

Received: Thu 28, Feb 2019Accepted: Sat 16, Mar 2019

Published: Sat 06, Apr 2019

Copyright

© 2023 Kostas Kapellas . This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.DOBCR.2019.01.005

Author Info

Xiangqun Ju Kostas Kapellas Lisa M. Jamieson Nicole Mueller Xiaoyan Wang

Corresponding Author

Kostas KapellasAustralian Research Centre for Population Oral Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia

Figures & Tables

Table 1: Studies on the association between dementia and periodontal disease

|

Author/year |

Country |

Sample Size |

Study Design |

Dementia Definition |

PD Definition |

Main finding |

|

Ship 1994 |

USA |

Total N=42 mean age 65 years (range 48-90) Alzheimer’s Disease N=21 without Alzheimer’s Disease N=21 |

C/C |

NINCDS-ADRDA MMSE for severity

|

PI, GB, PPD, LOA |

Oral health parameters including tooth surfaces with dental plaque, sites with gingival bleeding and calculus were significantly worse in the AD group compared to control. Non-significant trend for poorer gingival health with lower MMSE scores. No significant difference in PPD, recession and LOA between AD and controls. |

|

Syrjälä 2007 |

Finland |

Total N=2,320 aged ≥55 years MMSE 16-12 N=1,892 MMSE 11-10 N=297 MMSE ≤ 9 N=131 |

C/S |

Shortened MMSE: Cognitive impairment = ≤11 |

≥1 site PPD ≥4mm |

People with mild-severe cognitive impairment had, on average, fewer teeth in total and more carious teeth than ‘healthy’ people. There were fewer teeth with PPD ≥4mm among individuals with cognitive impairment mean (SD) 3.7 (4.7) compared to ‘healthy’ people 4.6 (5.5). |

|

Yu 2008 |

Taiwan |

Total N=803 aged ≥60 years DSST Score <34 Q1 N=233 DSST Score 34-45 Q2 N=193 DSST Score 46-57 Q3 N=188 DSST Score >57 Q4 N=199 |

C/S |

DSST: No cut-off score provided. Higher scores indicate higher cognitive function |

PPD ≥3mm, ≥10% sites CAL ≥4mm, ≥10% sites not on same site or tooth |

Periodontal disease was more common in people with low DSST scores. Odds of periodontal disease with increasing (continuous) DSST score 0.69 (95% CI 0.51-0.94), P=0.02. Compared to Q1: Q2 OR 0.60 (95% CI 0.34-1.08), Q3 0.54 (95% CI 0.28-1.07), Q4 0.43 (95% CI 0.18-1.02); P trend=0.04. |

|

Kaye 2010 |

USA |

Total N=597 men aged 28-70 years MMSE: Low N=95, Normal N=500 SCT: Low N=185, Normal N=412 |

Co |

MMSE: Cognitive impairment = <25; SCT: Cognitive impairment = <10 |

CPI score ≥ 2 PPD & Recession >1mm |

Trend for higher mean PPD ≥4mm among men with ‘low’ MMSE & SCT scores compared to ‘normal’. Progression of PD stratified by median age 45.5years: 10-year adjusted HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.01-1.09) for PD progression for ‘low’ MMSE score; 10-year adjusted HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.01-1.06) for PD progression for ‘low’ SCT score. |

|

Rai 2012 |

India |

Total N=107 Dementia N=20 (age range 59-69 years) Healthy control N=32 (age range 58-69 years) Severe periodontitis N=55 (age range 60-69 years) |

C/C |

|

Dental plaque, GI, BOP, PPD & CAL. |

Adjusted for age: dental plaque, GI, BOP, PPD & CAL significantly higher for people with dementia and periodontitis compared to controls. Mean PPD (SD) dementia: 4.81 (0.78), ‘severe periodontitis’: 2.85 (0.67), ‘healthy’: 1.89 (0.67). |

|

Kamer 2012 |

Denmark |

Total N=152 (aged 70 years)

|

C/S |

WAIS, DST: Cognitive impairment score <29 BDT: Cognitive impairment score <32 |

MCPI score ≥3 indicative of PPD ≥4mm |

70% of sample had MCPI. Mean (SD) DST score significantly lower for people with MCPI score ≥3: 33.4 (10.5) compared to 41.0 (10.7) for those with MCPI ≤2. Mean (SD) BDT score significantly lower for people with MCPI score ≥3: 31.2 (7.9) compared to 33.0 (6.8) for those with MCPI ≤2. Crude OR for ‘low’ DST score among MCPI score ≥3 =5.38 (95% CI 1.97-14.73). Crude OR for ‘low ’BDT score among MCPI score ≥3 =3.26 (95% CI 1.26-8.38) if lost <10 teeth, and BDT OR 0.41 (95% CI 0.84-2.04) if lost ≥11 teeth. |

|

Syrjälä 2012 |

Finland |

Total N=354 aged ≥75 years, mean (SD) 82.0 (4.9) years Without dementia N=278 AD N=49 Vascular dementia N=16 Other dementia type N=11 |

C/S |

DSM-IV: Dementia severity defined by DSM-III-R ‘mild’=33, ‘moderate’=24, ‘severe’=19 |

PPD ≥4mm |

49.2% of sample edentulous. Mean (SD) teeth of people with AD: 10.9 (7.0) compared to 15.0 (8.2) for those without dementia. Adjusted RR of PPD ≥4mm with AD: 1.4 (95% CI 0.9-2.1), other dementia types adjusted RR 2.5 (95% CI 1.5-4.1). Crude RR of PPD ≥4mm with ‘mild’ dementia: RR 1.4 (1.0–2.0), ‘moderate or severe’ dementia: RR 1.5 (1.0–2.1). |

|

Stewart 2013 |

USA |

Total N=1,053 aged 70-79 years, mean (SD) 73.5 (2.8) years

|

Co |

3MS: Cognitive impairment = score <80, DSST: 20% decline in 5-years |

PPD ≥3mm; LOA ≥3mm GI (0-3), plaque score & BOP |

Cognitive decline over 5 years reported in ascending order by oral health parameter quartile. Extent of PPD ≥3mm: Q1 4.5%, Q2 4.1%, Q3 2.6%, Q4 11.7%. Odds for cognitive decline per quartile increase in extent of PPD ≥3mm: OR 1.50 (95% CI 1.17–1.92); Gingival index score: Q1 2.0, Q2 3.9, Q3 6.1, Q4 15.5%. Odds for cognitive decline per quartile increase in GI: OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.66–2.67); |

|

Naorungroj 2013 |

USA |

Total N=5,878 aged 46-65 years, mean (SD) 56.8 (5.7) years

|

Co |

DWR, WF, DSST |

CDC/AAP ‘severe’ definition & gingival inflammation |

Cognitive decline over 6 years reported. All estimates adjusted for age, sex and race. Adjusted OR for ‘severe’ periodontitis: DWR: OR 1.01 (95% CI 0.94, 1.09); DSST: OR 1.08 (95% CI 1.01, 1.17) WF: OR 1.00 (95% CI 0.93, 1.07). Adjusted OR for ‘extent gingival inflammation’: DWR: OR 0.29 (95% CI -0.47, 1.06); DSST: OR 1.22 (95% CI 0.45, 1.99), WF: OR 0.66 (95% CI -0.09, 1.41). |

|

de Souza Rolim 2014

|

Brazil |

Total N=59 aged 59-91 years, Control group N=30 mean (SD) 61.2 (11.2) years Dementia group N=29 mean (SD) 75.2 (6.7) years |

C/C |

NINCDS-ADRDA criteria equivalent to MMSE scores 18-26 |

PI ≥30% GBI ≥20% PPD >3mm & CAL >3mm |

Periodontal infections were significantly more frequent in patients with dementia than in healthy subjects. 31% of dementia group had gingivitis compared to 10% of control group. 27.6% of dementia group had ‘moderate’/’severe’ periodontitis compared to 16.7% of control group. |

|

Martande 2014 |

India |

118 subjects: aged 50-80 years Dementia group N=58 mean (SD) 65.2 (7.3) years. Control group N=60 mean (SD) 64.5 (9.4) years |

C/S |

NINCDS-ADRDA MMSE scores: ‘mild’:21-25 N=22, ‘moderate’: 11-20 N=18, ‘severe’ ≤10 N=18 |

PI, GI, PPD, CAL, REC |

Oral health parameters stratified by MMSE scores. Mean (SD) GI scores: control 0.64 (0.21), ‘mild’ 1.15 (0.21), ‘moderate’ 1.68 (0.22), ‘severe’ 2.31 (0.26). Mean (SD) PPD scores: control 2.39 (0.55), ‘mild’ 3.18 (0.35), ‘moderate’ 3.99 (0.32), ‘severe’ 5.02 (0.56). |

|

Gil-Montoya 2015 |

Spain |

Total N=409 aged 51-98 years Control group N=229 mean (SD) 78.5 (7.9) years. Dementia group N=180 mean (SD) 77.0 (7.8) years.

|

C/C |

DSM-IV, NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. ‘mild’ cognitive impairment N=21, ‘mild/moderate’ dementia N=123, ‘severe’ dementia N=36 |

PI, BI, PPD, AL by % of sites with AL >3 mm as follows: 0%=Non-PD, ‘mild’ PD = 0-32%, ‘moderate’ PD = 33% - 66%, ‘severe’ PD = 67% to 100% |

People with cognitive impairment/dementia had significantly fewer teeth mean (SD) 15.3 (8.0) compared to controls 17.4 (8.0), P=0.008. Mean (SD) BI scores: control 50.6% (34.2), ‘cognitive impairment/dementia’ 63.0 (31.1), P=<0.001. Mean (SD) PPD scores: control 2.6 (1.5), ‘cognitive impairment/dementia’ 3.0 (0.7), P=<0.001. ‘Mod/severe’ AL more common among ‘cognitive impairment/dementia’ group 90% versus 75.5% for controls. Odds of ‘moderate’ AL 2.58 (95% CI 1.31 - 5.09), OR ‘severe’ AL 3.04; (95% CI 1.69 - 5.46). |

|

Cestari 2016 |

Brazil |

Total N=65 aged 56-92 years. AD N=25 mean (SD) 77.7 (6.0) years MCI N=19 mean (SD) 73.1 (6.8) years. Control group N=21 mean (SD) 75.3 (5.8) years |

C/C

|

NINCDS-ADRDA |

PI, BI, PPD, CAL |

Study compared people with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment to ‘healthy’ controls. No significant difference between the three groups in terms of periodontitis case: AD 40.0%, MCI 26.3%, ‘healthy’ 42.5%. Mean PPD was also non-significantly difference between the three groups mean (SD): AD 2.8 (1.7), MCI 3.1 (1.6), ‘healthy’ 2.6 (3.3). |

|

Shin 2016 |

Korea |

Total N=189 aged 60-86 years. Cognitively impaired N=65 mean (SD) 69.7 (6.4) years Cognitively normal N=124 mean (SD) 68.7 (4.9) years. |

C/C |

MMSE-KC |

‘moderate’ PD ≥2 interproximal sites with RABL ≥4 mm), ‘severe’ PD ≥2 interproximal sites with RABL≥6 mm |

More people with cognitive impairment had periodontitis 36.9% compared to those cognitively normal 23.4%, P=0.049. People with a history of periodontitis were more likely to have cognitive impairment: adjusted OR: 2.14 (95% CI 1.04-4.41). |

|

Zenthöfer 2017 |

Germany |

Total sample N=219 aged 54-102 years Dementia N=136 mean (SD) 84.6 (8.1) years Non-dementia N=83 mean (SD) 80.7 (9.8) years |

C/S

|

MMSE score <20 |

GBI, CPITN, DHI ‘Moderate’ periodontitis: codes 1-3 ‘Severe’ periodontitis: code 4 |

42% of sample edentulous. Mean (SD) CPITN score significantly higher among dementia group 3.1 (0.7) compared to non-dementia group 2.7 (0.6), P <0.01. Non-significant difference in GBI scores between dementia mean (SD) 53.8 (27.6) compared to non-dementia 48.8 (28.9). ‘Severe’ periodontitis was more common: OR 2.9 (1.4- 6.3) among people with dementia. Dementia does not influence GBI OR: 0.5 (-8.6-12.5). |

|

Nilsson 2018 |

Sweden |

Total N=704 aged 60-96 years. Cognitive decline N=115 No decline N=589 |

Co |

MMSE ≥3 points deterioration over six years |

≥4mm bone loss at ≥30% of tooth sites |

83% of those with cognitive decline aged ≥72 years. 59% of people experiencing cognitive decline had periodontal bone loss which was significantly higher than the 34% without cognitive decline P<0.01 Odds of cognitive decline among those with periodontal disease: Adjusted OR 2.0 (95% CI 1.2-3.3). |

C/S: cross-sectional, C/C: case-control, Co: cohort, RR: risk ratio, OR: Odds Ratio, HR: hazard ratio, SD: standard deviation, CI: confidence interval.

ABL: alveolar bone loss, AL: attachment loss, BI: bleeding index, BOP: bleeding on probing, CAL: clinical attachment level, CDC/AAP: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology CP: chronic periodontitis, CPITN: community periodontal index of treatment need, GBI: gingival bleeding index, GI: gingival index, LOA: loss of attachment, MCIP: modified community periodontal index, PD: periodontal disease, PI: plaque index, PPD: probing pocket depth, RABL: radiographic alveolar bone loss.

3MS: Modified mini mental state examination, WAIS: Wechsler adult intelligence scale, MMSE: mini-mental state examination, SCT: spatial copying task, DSST(DHI: denture hygiene index, DST): digit symbol substitution test, BDT: block design test, DSM-IV: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, DSM-III-R: diagnostic and mental Disorders, DWR: delayed words recall, WF: word fluency, Clinical Modification, (NINCDS-ADRDA): Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders association, MMSE-KC: mini-mental state examination Korean version, D: Dementia, ND Non-Dementia, AD: Alzheimer’s Disease, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, ADAS-cog: Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale.

Table 2: Studies on the association between periodontal disease and dementia

|

Author/year |

Country |

Sample Size |

Study Design |

Dementia Definition |

PD Definition |

Main finding |

|

Tzeng 2016 |

Taiwan |

Total N= 8,828 aged ≥20 years. Periodontitis cases N=2,207 Non-periodontitis cases N=6,621

|

Co |

DSM-IV |

ICD-9-CM codes: 523.4 (chronic periodontitis) and 523.1 (chronic gingivitis) |

25 (1.1%) of periodontitis cases developed dementia over a 10-year period compared to 61 (0.9%) on non-periodontitis cases, P=0.04. Adjusted HR: 2.54 (95% CI 1.55–4.16) equivalent to 510.6/100,000 population periodontitis cases compared to 248.9/100,000 population for non-periodontitis cases. |

|

Iwasaki 2016 |

Japan |

Total N=85 mean (SD) 79.3 (3.7) years. Non-severe PD N=64 Severe PD N=21 |

Co

|

MMSE must have score ≥24 at baseline. |

CDC/AAP ‘severe’ classification |

Three-year follow-up period. No significant difference between mean (SD) MMSE scores: Non-severe PD: 27.6 (1.9), severe PD: 27.6 (2.1). ‘Severe’ periodontitis was associated with increased risk of MMSE decline over 3 years relative to ‘non-severe’ periodontitis: Adjusted RR 2.2 (95% CI 1.1-4.5) |

|

Ide 2016 |

UK |

Total N=52 mean (SD) 77.7 (8.6) years. Periodontitis cases N=20 mean (SD) 74.9 (2.0) years. Non-periodontitis cases N=32 mean (SD) 79.4 (1.3) years. |

Co

|

NINCDS-ADRDA (ADAS-COG, MMSE) |

CDC/AAP |

No significant difference in baseline MMSE scores between periodontitis mean (SD) 19.5 (1.0) and non-periodontitis groups 21. (0.9). No significant difference in baseline between ADAS-COG scores between periodontitis mean (SD) 46.8 (2.2) and non-periodontitis groups 45.7 (2.2).

Study participants followed-up for 6-months: significant change in ADAS-COG score: between group adjusted mean (95% CI) 4.9 (1.2 – 8.6). Non-significant change in sMMSE score between group mean (95%) -1.8 (-3.6-0.04). |

|

Chen 2017 |

Taiwan |

Total N=27,963 aged ≥50 years. With chronic periodontitis N=9,291 mean (SD) 54.1 (10.5) years. Without chronic periodontitis N=18,672 mean (SD) 54.2 (10.5) years. |

Co |

AD (ICD-9-CM code 331.0) |

Chronic periodontitis (ICD-9-CM code 523.4) |

Study participants followed-up over mean 12 years. 1-year risk of Alzheimer’s disease risk among people with periodontitis: adjusted HR: 1.30 (1.00–1.70). 10–year risk of Alzheimer’s disease risk among people with periodontitis: HR: 1.71 (1.15–2.53). |

|

Lee 2017 |

Taiwan |

Total N-6,056 aged ≥65 years. With periodontitis N=3,028 mean 72.4 years. Without periodontitis N=3,028 mean 72.4 years. |

Co |

AD (ICD-9-CM codes 290.0-290.4, 294.1, 331.0-331.2) |

Chronic periodontitis (ICD-9-CM code 523.3-5) |

Follow-up period not explicitly stated but is ~8 years. Periodontitis and non-periodontitis comparable at baseline except for geographical location or residence. Adjusted HR for dementia among those with periodontitis: 1.16 (95% CI 1.01-1.32). |

|

Lee 2017 |

Taiwan |

Total N=182,747 with periodontitis aged ≥45 years. Dental prophylaxis N=97,802 Intensive periodontal treatment N=5,373 Tooth extraction(s) N=59,898 No treatment N=19,674 |

Co |

AD (ICD-9-CM codes 290.0-290.4, 294.1, 331.0) |

ICD-9-CM code 523.0-523.5 |

10-year follow-up period. 6,133 developed dementia, resulting in an IR for dementia of 0.47%/year. Adjusted HRs for dementia based on treatment received: intensive treatment: HR 1.18 (0.97-1.43), extraction: HR 1.10 (1.04-1.16), no treatment: HR 1.14 (1.04-1.24). |

|

Iwasaki 2018 |

Japan |

Total N=179 aged ≥75 years, mean (SD) 80.1 (4.4) years. CDC/AAP ‘severe’ N=49 mean (SD) age 79.9 (4.0) CDC/AAP ‘non-severe periodontitis’ N=130 mean (SD) age 80.2 (4.6) |

Co |

MMSE & DSM-IV |

EWP & CDC/AAP ‘severe’ classifications |

5-year follow up period. Adjusted OR for MCI based on EWP ‘severe’ periodontitis definition: 3.58 (95% CI 1.45-8.87) compared to ‘non-severe’ periodontitis. Adjusted OR for MCI based on CDC/AAP ‘severe’ periodontitis definition: 2.61 (95% CI 1.08-6.28) compared to ‘non-severe’ periodontitis. |

Co: cohort, RR: risk ratio, OR: Odds Ratio, HR: hazard ratio, IR: incidence ratio, SD: standard deviation, CI: confidence interval.

CDC/AAP: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology, CP: chronic periodontitis, EWP: European Workshop on Periodontitis, PD: periodontal disease.

ADAS-cog: Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale, DSM-IV: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, MMSE: mini-mental state examination, (NINCDS-ADRDA): Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders association.

References

- Armitage GC (2002) Classifying periodontal diseases--a long-standing dilemma. Periodontol 2000 30: 9-23. [Crossref]

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ, et al. (2012) Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res 91: 914-920. [Crossref]

- Roberts Thomson K, Do L (2007) Oral Health Status In: Slade G, Spencer A, Roberts-Thomson K, editors. Australia’s dental generations: the National Survey of Adult Oral Health 2004-06. Dental Statistics and Research Series No. 34. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 119.

- Cerajewska TL, Davies M, West NX (2015) Periodontitis: a potential risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Br Dent J 218: 29-34. [Crossref]

- Selkoe DJ (2011) Alzheimer's disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives Biology 3.

- Galimberti D, Scarpini E (2012) Progress in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol 259: 201-211. [Crossref]

- Crasta K, Daly C, Mitchell D, Curtis B, Stewart D, et al. (2009) Bacteraemia due to dental flossing. J Clin Periodontol 36: 323-332. [Crossref]

- Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Sasser HC, Fox PC, Paster BJ, et al. (2008) Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation 117: 3118-31125. [Crossref]

- Forner L, Larsen T, Kilian M, Holmstrup P (2006) Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontol 33: 401-407. [Crossref]

- Geerts S, Nys M, De Mel P, Charpentier J, Albert A, et al. (2002) Systemic Release of Endotoxins Induced by Gentle Mastication: Association with Periodontitis Severity. J Periodontol 73: 73-78. [Crossref]

- Brodala N, Merricks EP, Bellinger DA, Damrongsri D, Offenbacher S, et al. (2005) Porphyromonas gingivalis Bacteremia Induces Coronary and Aortic Atherosclerosis in Normocholesterolemic and Hypercholesterolemic Pigs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1446-1451. [Crossref]

- Lalla E, Lamster IB, Hofmann MA, Bucciarelli L, Jerud AP, et al. (2003) Oral Infection with a Periodontal Pathogen Accelerates Early Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Null Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1405-1411. [Crossref]

- Pussinen PJ, Jousilahti P, Alfthan G, Palosuo T, Asikainen S, et al. (2003) Antibodies to Periodontal Pathogens Are Associated with Coronary Heart Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1250-1254. [Crossref]

- Chen CK, Wu YT, Chang YC (2017) Association between chronic periodonJ Clin Periodontoltitis and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective, population-based, matched-cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 9: 56. [Crossref]

- Kozarov EV, Dorn BR, Shelburne CE, Dunn WA, Progulske Fox A (2005) Human Atherosclerotic Plaque Contains Viable Invasive Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 17-18. [Crossref]

- Poole S, Singhrao SK, Kesavalu L, Curtis MA, Crean S (2013) Determining the presence of periodontopathic virulence factors in short-term postmortem Alzheimer's disease brain tissue. J Alzheimers Dis 36: 665-677. [Crossref]

- Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, et al. (2017) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses 2014.

- Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, et al. (2013) Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? a systematic review. BMC Public Health 13: 154. [Crossref]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR (2009) Identifying and quantifying heterogeneity. Introduction to meta‐analysis: John Wiley and Sons 107-125.

- Borenstein M, Higgins JPT, Hedges LV, Rothstein HR (2017) Basics of meta-analysis: I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods 8: 5-18. [Crossref]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6: e1000097. [Crossref]

- Cestari JA, Fabri GM, Kalil J, Nitrini R, Jacob-Filho W, et al. (2016) Oral Infections and Cytokine Levels in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment Compared with Controls. J Alzheimers Dis 52: 1479-1485. [Crossref]

- de Souza Rolim T, Fabri GM, Nitrini R, Anghinah R, Teixeira MJ, et al. (2014) Oral infections and orofacial pain in Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study. J Alzheimers Dis 38: 823-829. [Crossref]

- Gil-Montoya JA, Sanchez-Lara I, Carnero-Pardo C, Fornieles F, Montes J, et al. (2015) Is periodontitis a risk factor for cognitive impairment and dementia? A case-control study. J Periodontol 86: 244-253. [Crossref]

- Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, Sussams R, Hopkins V, et al. (2016) Periodontitis and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One 11: e0151081. [Crossref]

- Iwasaki M, Kimura Y, Ogawa H, Yamaga T, Ansai T, et al. (2018) Periodontitis, periodontal inflammation, and mild cognitive impairment: A 5‐year cohort study. J Periodontal Res 21. [Crossref]

- Iwasaki M, Yoshihara A, Kimura Y, Sato M, Wada T, et al. (2016) Longitudinal relationship of severe periodontitis with cognitive decline in older Japanese J Periodontal Res 51:681-688. [Crossref]

- Kamer AR, Morse DE, Holm-Pedersen P, Mortensen EL, Avlund K (2012) Periodontal inflammation in relation to cognitive function in an older adult Danish population. J Alzheimers Dis 28: 613-624. [Crossref]

- Kaye EK, Valencia A, Baba N, Spiro A, Dietrich T, et al. (2010) Tooth loss and periodontal disease predict poor cognitive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 713-718. [Crossref]

- Lee YL, Hu HY, Huang LY, Chou P, Chu D (2017) Periodontal Disease Associated with Higher Risk of Dementia: Population‐Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc 65: 1975-1980. [Crossref]

- Lee YT, Lee HC, Hu CJ, Huang LK, Chao SP, et al. (2017) Periodontitis as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Dementia: A Nationwide Population‐Based Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 65: 301-305. [Crossref]

- Martande SS, Pradeep AR, Singh SP, Kumari M, Suke DK, et al. (2014) Periodontal health condition in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 29: 498-502. [Crossref]

- Naorungroj S, Slade GD, Beck JD, Mosley TH, Gottesman RF, et al. (2013) Cognitive decline and oral health in middle-aged adults in the ARIC study. J Dent Res 92: 795-801. [Crossref]

- Nilsson H, Berglund JS, Renvert S (2018) Longitudinal evaluation of periodontitis and development of cognitive decline among older adults. J Clin Periodontol 45: 1142-1149. [Crossref]

- Rai B, Kaur J, Anand SC (2012) Possible relationship between periodontitis and dementia in a North Indian old age population: a pilot study. Gerodontology 29: 200-205. [Crossref]

- Sacco R, Boden-Albala B, Gan R, Chen X, Kargman D, et al. (1998) Stroke incidence among white, black, and Hispanic residents of an urban community: The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Am J Epidemiol 147: 259-268. [Crossref]

- Shin HS, Shin MS, Ahn YB, Choi BY, Nam JH, et al. (2016) Periodontitis Is Associated with Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Koreans: Results from the Yangpyeong Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 64: 162-167. [Crossref]

- Ship JA, Puckett SA (1994) Longitudinal study on oral health in subjects with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 42: 57-63. [Crossref]

- Stewart R, Weyant RJ, Garcia ME, Harris T, Launer LJ, et al. (2013) Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 177-184. [Crossref]

- Syrjala AM, Ylostalo P, Ruoppi P, Komulainen K, Hartikainen S, et al. (2012) Dementia and oral health among subjects aged 75 years or older. Gerodontology 29: 36-42. [Crossref]

- Syrjala AM, Ylostalo P, Sulkava R, Knuuttila M (2007) Relationship between cognitive impairment and oral health: results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand 65: 103-108. [Crossref]

- Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Yeh CB, Huang RY, Yuh DY, et al. (2016) Are Chronic Periodontitis and Gingivitis Associated with Dementia? A Nationwide, Retrospective, Matched-Cohort Study in Taiwan. Neuroepidemiology 47: 82-93. [Crossref]

- Yu YH, Kuo HK (2008) Association between cognitive function and periodontal disease in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 1693-1697. [Crossref]

- Zenthofer A, Baumgart D, Cabrera T, Rammelsberg P, Schroder J, et al. (2017) Poor dental hygiene and periodontal health in nursing home residents with dementia: an observational study. Odontology 105: 208-213. [Crossref]

- Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, Sussams R, Hopkins V, et al. (2016) Periodontitis and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. PLoS One 11: e0151081. [Crossref]

- Gusman DJR, Mello-Neto JM, Alves BES, Matheus HR, Ervolino E, et al. (2018) Periodontal disease severity in subjects with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 76: 147-159. [Crossref]

- Leira Y, Domínguez C, Seoane J, Seoane-Romero J, Pías-Peleteiro JM, et al. (2017) Is Periodontal Disease Associated with Alzheimer's Disease? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology 48: 21-31. [Crossref]

- Maldonado A, Laugisch O, Bürgin W, Sculean A, Eick S (2018) Clinical periodontal variables in patients with and without dementia—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Invest 22: 2463-2474. [Crossref]

- Tonsekar PP, Jiang SS, Yue G (2017) Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology 34: 151-163. [Crossref]

- Noble JM, Borrell LN, Papapanou PN, Elkind MS, Scarmeas N, et al. (2009) Periodontitis is associated with cognitive impairment among older adults: analysis of NHANES-III. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80: 1206-1211. [Crossref]

- Kamer AR, Pirraglia E, Tsui W, Rusinek H, Vallabhajosula S, et al. (2015) Periodontal disease associates with higher brain amyloid load in normal elderly. Neurobiol Aging 36: 627-633. [Crossref]

- Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Meijer J, Kiliaan A, Ruitenberg A, et al. (2004) Inflammatory proteins in plasma and the risk of dementia: the rotterdam study. Arch Neurol 61: 668-672. [Crossref]

- Holmes C, El-Okl M, Williams AL, Cunningham C, Wilcockson D, et al. (2003) Systemic infection, interleukin 1beta, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74: 788-789. [Crossref]

- Watts A, Crimmins EM, Gatz M (2008) Inflammation as a potential mediator for the association between periodontal disease and Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 4: 865-876. [Crossref]

- Southerland J, Taylor G, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S (2006) Commonality in chronic inflammatory diseases: periodontitis, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Periodontol 2000 40: 130-143. [Crossref]

- Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE (2014) Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000 64: 57-80. [Crossref]